After asking Fassbender about the last person to see Teresa Halbach alive being an obvious place to start, kRATz makes the exaggerated check-mark motion on his note pad. He did that sickening motion numerous times. It is a sign of utter arrogance. So infantile. Can you imagine his bullet list?

- Ask Fassy super smart question.

- Sweat.

- Petty objection.

- Sweat some more.

- Send dickpic.

- Sweat so much I feel drips tickle my crack as they run down my back.

- Erection!

"The way I hear it, Kenny was indeed offering up his 'services' to a whole list of domestic abuse victims... pro boner... cost him a 4-month suspension, 20k, his marriage, his house, his reputation, and any semblance of integrity remaining in his horrific existence...he's THE PRIZE... LOL." [HuNuWutWen]Click here for Associated Press reporter Ryan Foley's audio interview of Ken Kratz.

"I am the most notable prosecutor in Wisconsin history because of the Steven Avery case." - Ken Kratz, May 2010 (page 19)

"He [Ken Kratz] would remind me of who he was, how he had prosecuted the biggest case around here, and what a 'prize' he was." - Dawn King, September 24, 2010 (page 14)

A domestic violence victim who turned to Kratz’s office for help claims that the DA sexually harassed her via numerous text messages, trying to convince her to have an affair with him. One of his texts read, in pertinent part:

“I’m the atty. I have the $350,000 house. I have the 6-figure career. You may be the tall, young, hot nymph, but I am the prize!”

Stephanie Van Groll: "Three Days of Hell" When Wis. DA Kenneth Kratz "Sexted" Her

Domestic abuse victim Stephanie Van

Groll and Calumet County, Wisc. District Attorney Kenneth Kratz are seen

in file photos. Katz "sexted" Van Groll repeatedly while prosecuting

her alleged assailant, threatening to drop the case if she didn't engage

in a sexual relationship. (AP Photo)

September 15, 2010

A prominent Wisconsin district attorney sent repeated text messages trying to spark an affair with a domestic abuse victim while he was prosecuting her ex-boyfriend, a police report shows.

The 26-year-old woman complained last year to police after receiving 30 texts from Calumet County District Attorney Kenneth Kratz in three days, according to the report obtained by The Associated Press.

"Are you the kind of girl that likes secret contact with an older married elected DA ... the riskier the better?" Kratz, 50, wrote in a message to Stephanie Van Groll in October 2009. In another, he wrote: "I would not expect you to be the other woman. I would want you to be so hot and treat me so well that you'd be THE woman! R U that good?"

Kratz was prosecuting Van Groll's ex-boyfriend on charges he nearly choked her to death last year. He also was veteran chair of the Wisconsin Crime Victims' Rights Board, a quasi-judicial agency that can reprimand judges, prosecutors and police officers who mistreat crime victims.

In a combative interview in his office Wednesday, Kratz did not deny sending the messages and expressed concern their publication would unfairly embarrass him personally and professionally. He said the Office of Lawyer Regulation had found he did not violate any rules governing attorney misconduct. That office cannot comment on investigations.

"This is a non-news story," Kratz shouted. But he added, "I'm worried about it because of my reputational interests. I'm worried about it because of my 25 years as a prosecutor."

'Three days of hell'

Van Groll told police in Kaukauna, Wis., where she lived, that she felt pressured to have a relationship with Kratz or he would drop the charges against her ex-boyfriend.

By The Associated Press

March 28, 2011

A former prosecutor who sent racy text messages to a domestic abuse victim will not face criminal charges over misconduct and sexual assault allegations levied by more than a dozen women, the Wisconsin Justice Department announced Monday.

State investigators determined that former Calumet County District Attorney Ken Kratz’s “conduct appears to fit the connotation of ‘misconduct’ and demonstrates inappropriate behavior but does not satisfy the elements required to prosecute,” wrote Assistant Attorney General Tom Storm.

Kratz’s attorney, Robert Bellin, said his office was investigating whether anyone lied in an effort to hurt Kratz.

“I think it’s obviously the right decision,” Bellin said of not filing charges. “I don’t think we were that worried about it. We think that there were statements from individuals who came forward who were not completely truthful.”

Kratz resigned from his $105,000 per year position in October after The Associated Press reported he had sent 30 text messages trying to strike up an affair with a domestic abuse victim while he prosecuted her ex-boyfriend on a strangulation charge. Kratz, who was 50 at the time, called 26-year-old Stephanie Van Groll “a hot nymph” and asked if she was “the kind of girl that likes secret contact with an older married DA.”

Van Groll complained to police and Kratz was removed from her ex-boyfriend’s case. The Justice Department investigated at the time but decided not to file charges. Kratz was instead ordered to self-report the text messages to the Office of Lawyer Regulation, a separate state entity that reviews attorneys’ conduct. The office declined to discipline Kratz, saying he hadn’t violated any rules.

Pressure mounted on Kratz to resign after Van Groll’s allegations became public. Then-Gov. Jim Doyle began removal procedures and other women came forward with accusations. The Justice Department and the lawyer regulation office both reopened investigations.

The Justice Department on Monday released its case summary, which said Van Groll was among a dozen or so women who complained about Kratz.

Two claimed they had sexual contact with Kratz, five alleged misconduct in office, and one alleged Kratz improperly told her about a search warrant. The remaining complaints didn’t include an identifiable criminal offense, the report said.

Storm, who led the investigation, wrote that one of the alleged sexual encounters occurred in 1999 and the statute of limitations had expired. The other sexual contact complaint contained “insurmountable proof problems,” Storm wrote, adding the woman wouldn’t be a credible witness because she suffered from mental illness, had prior convictions and consented to the contact.

As for misconduct in office, complaints included the messages Kratz sent to Van Groll as well as accusations Kratz sought a personal relationship with one woman in exchange for help in winning a gubernatorial pardon and a relationship with another woman in exchange for help writing a victim impact statement against her husband.

But investigators found Kratz technically didn’t fail or refuse to perform his duties, didn’t exceed his authority and didn’t try to gain a dishonest advantage.

A woman also alleged that while she was out to eat with Kratz, he was on the phone with investigators discussing a search that was under way, possibly in connection with a search warrant. Wisconsin law prohibits premature disclosure of a search warrant’s existence. But the woman couldn’t say that Kratz actually disclosed a warrant existed at any time.

“There is no reasonable possibility that further investigation will reveal evidence establishing the elements of a criminal offense,” Storm wrote. “There are no further leads to pursue and the file should be closed.”

Separately, Van Groll has filed a federal civil lawsuit accusing Kratz of sexual harassment. Van Groll’s attorney, Michael Fox, didn’t immediately return a message Monday.

Further allegations against 'sexting' DA claim social invitation to an autopsy

By The Wisconsin State Journal

September 21, 2010

Weeks after Calumet County District Attorney Kenneth Kratz was caught sending sexually charged text messages to a crime victim, he shared confidential details of a murder investigation with another woman and invited her to wear high heels to the victim's autopsy, according to a letter obtained Monday by the Wisconsin State Journal.

September 21, 2010

Weeks after Calumet County District Attorney Kenneth Kratz was caught sending sexually charged text messages to a crime victim, he shared confidential details of a murder investigation with another woman and invited her to wear high heels to the victim's autopsy, according to a letter obtained Monday by the Wisconsin State Journal.

In the letter sent to Gov. Jim Doyle on Friday, the woman called for Kratz's removal from office and an investigation into why the district attorney was not sanctioned for his improper attempts to strike up a sexual relationship with Stephanie Van Groll, whose ex-boyfriend Kratz was prosecuting on domestic abuse charges

The woman could not be reached for comment Monday. However, Doyle spokesman Adam Collins released a copy of the letter to the media Monday afternoon - with the woman's name blacked out - shortly before Doyle announced he would seek to remove Kratz once he receives a "verified" complaint from a taxpayer in Calumet County. Van Groll lives in a different county.

Kratz, who has held his position for 18 years, has apologized for sending the text messages and said he would seek therapy. He began a medical leave on Monday, but his attorney has said he would fight attempts to remove him from office.

Kratz was also pressured to resign from the Crime Victims Rights Board, which he had chaired for 11 years, on Dec. 3 after Van Groll called Kaukauna police to report that Kratz had been harassing her by sending 30 text messages in three days.

Last week, another woman wrote to Doyle's office to say she had had a similar experience with Kratz, 50, after the two met on the online dating service Match.com in December.

"We exchanged a few emails and eventually agreed to meet for dinner," she wrote. "I was hesitant since he had written some things that were inappropriate to say to someone at that stage of communicating, and also seems to vacillate between kind and interesting and insecure, impatient and demanding. But I figured that as a public figure in a position of authority, I should be safe with him."

Later in the letter, the woman recounts incidents that appear to match the circumstances surrounding the case of Michelle Jaeger, a 39-year-old Chilton woman who disappeared in early January. Her body was found on Jan. 24, and Manitowoc County District Attorney Mark Rohrer has charged her former boyfriend, Roger D. Rosenthal, with first-degree intentional homicide. Jaeger's body was found near Brillion in Manitowoc County.

"We met for dinner at a restaurant in Green Bay on January 23, 2010," the woman wrote. "During dinner he was interrupted several times by phone calls from Detectives who were investigating a case of a missing woman who was suspected of having been killed by her boyfriend.

"I told him that if he needed to step away to have a private discussion, I didn't mind. He had no problem talking to them in front of me and then sharing the details with me as well. Many of the details that had not been made available to the public, as I later found out as I watched the news and searched reports on the Internet."

In the days following, the woman said Kratz kept her updated on the murder investigation "and even went so far as to inviting me to go with him to the autopsy (provided I would be his girlfriend and would wear high heels and a skirt)."

According to the Chilton Times Journal, Jaeger's autopsy was scheduled for Jan. 26.

The woman said she also felt harassed by text messages she received from Kratz, which appear to bear a strong resemblance to the texts the prosecutor sent to the abuse victim last October. She eventually told him to stop contacting her.

"If I didn't answer his texts immediately, he would become insecure and question why I hadn't responded and would attack me or my character," she wrote. "He would remind me of who he was, how he had prosecuted the biggest case around here and what a ‘prize' he was."

She ended the letter to Doyle by saying, "Please take action and do the right thing."

On Monday afternoon, Doyle said his office had not yet checked out the woman's allegations but called them "very troubling" and said officials would investigate. He added he found it "unimaginable" and "mind-boggling" that Kratz may have used his job, especially access to a victim's body, as a lure to become involved with the woman.

"To have an autopsy used as a premise for a social engagement, it's just beyond anything anybody could imagine," Doyle said.

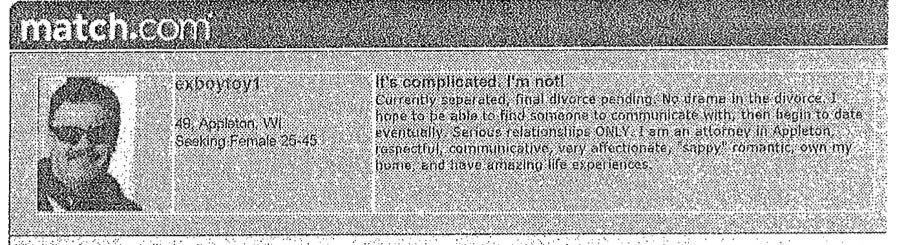

The Sexting DA's Romantic Adventures On Match.com

By Jezebel

April 4, 2011

The Wisconsin Dept. of Justice has released details of its investigation of sexting DA Kenneth Kratz. In addition to disturbing allegations by a variety of women, investigators found Kratz's Match.com profile and messages. Kratz's username: exboytoy1.

In addition to his repeated and unwanted sexting of Stephanie Van Groll, Kratz was accused of inviting a woman on a date to an autopsy, and pressuring another woman to have sex with him so he would support her pardon.

In addition to these, documents released Friday discuss new allegations. One woman says Kratz made "sexual advances" her while he was prosecuting her husband, including asking her to listen while he described "sexual scenarios" over the phone, offering to "send [her] to Chicago to learn how to be submissive" and fondling her under her skirt (this was consensual).

A social worker accuses him of sending inappropriate emails (more on this below).

A woman whom Kratz had prosecuted said he told her to perform oral sex on him or he could "get her jammed up" (this woman was apparently deemed an unreliable witness because she has mental illness and a criminal record).

Several women came forward with other complaints — one said Kratz asked her 17-year-old daughter inappropriate questions after she was the victim of a sex offender, while another said Kratz once told her, at work, "I won't cum in your mouth."

Several of the women above saved email correspondences between themselves and Kratz, and the woman he asked on the autopsy date saved their Match.com correspondence.

Here's Kratz's profile summary:

If you're having trouble reading the grey-on-grey, the text reads:

It's complicated, I'm not!By January 2010, when Kratz began messaging the woman in question, these "amazing life experiences" already included several alleged incidents of harassment, including the 30 racy text messages he sent to Stephanie Van Groll in 2009 (he wasn't kidding about being communicative). It may also be true that his divorce was drama-free, but he failed to mention that it was his third. Complicated indeed!

Currently separated, final divorce pending. No drama in the divorce. I hope to be able to find someone to communicate with, then begin to date eventually. Serious relationships ONLY. I am an attorney in Appleton, respectful, communicative, very affectionate, "sappy" romantic, own my home, and have amazing life experiences.

Here's the first message the woman provided, sent by Kratz on January 8:

ironic

Its [sic, as is everything else from here on out] ironic that the woman who probably struck the sharpets chord with me is the one that I find most interesting. The fact that you accepted my explaination (despite the twinge of arrogance left therein) demonstrates the depth of your personality...any assumption that I made about you skaking through life on your looks has been dispelled.

Not only would I welcome an opportunity to meet you for some conversation, I'd be honorred.

[Name redacted], you have left an impression with me that is far removed from the plastic coated responses I otherwise receive...even the women who are "thrilled" to talk to me have a veneer of animation to them. There is nothing fake about you.

Thank you for your response. You are a stunning and impressive woman. I would live to take you to dinner. Write soon. Thank you.

KenThe fact that the woman in question both struck a chord with Kratz and interested him does not appear to be ironic, but what is ironic is that Kratz fancied himself something of a writing expert, mocking a social worker (not his Match.com contact) for using the word "conflictual" in a report. He said it wasn't a word; it is one. Unlike, say, "skaking." When the social worker set him straight about "conflictual," he replied "you can either flirt with me or not — you can't have it both ways." She told him she wasn't interested in flirting, and the matter dropped, although she says he did comment to her about a reporter who had "big, beautiful breasts."

But back to the Match.com story — here's Kratz's next message (sent at 12:45 AM on Jan. 12):

Re: ironic

Wednesday? Let me know if we can do it before you leave—-Im hungry!

By the way is this a date (where I get to hold out hope of seeing you eventually) or a lunch with a possible friend thing, where I get to see how beautiful you are but realize that never in a million years will you be holdingher???

I have so many questions for you, seems you wont get in any edgewise!!!

If we do go to dinner and its a date, can I pick out the heels you will wear? I find that entertaining!

OK, talk soon, my phone [redacted by DOJ]...text or call anytime!!!

KenKratz appears to have been quite the fan of heels — he'd subsequently ask her to wear them to a crime scene, and later to the autopsy (she declined both). At 7:57 the next morning, he apparently felt he had come on a little strong:

plans

I re-read my message from last night. Guess I was a little impatient.

OK, lets try this again... If you have to leave town, just call next week when we can schedule something! I am truly looking forward to taking you to a lovely dinner (I'm sure whatever heels you pick will be beautiful—-LOL).

Regarding whether this is a "date" or not, we are both single and if there is some spark great, we'll go from there. If not, you will always have me available as a friend of yours. We don't have to "call" this anything! Call or text me.

Better?

KenAnd finally:

RE: plans

If I get 1 meal with you, dinner for sure! Friday or Saturday is best...but I will make myself available when you are free. What kind of food do you like? Green Bay, Appleton, in between...everything works.

I am a little "taken" by you. Im sorry I sound like Im in 7th grade. Obvious that doesn't happen to me very often

Let me know, and Im there! Thanks again..

KenKen and the woman did end up having dinner at the Black and Tan restaurant in Green Bay, and it was there that he — according to her testimony — took several phone calls and discussed an ongoing missing-person investigation with detectives while at the table with her. He also told her he suspected that the missing woman's boyfriend had murdered her, and invited her to the crime scene (in heels, natch), all while getting increasingly drunk. She says "DA Kratz was not worried about drinking and driving, and she felt he thought he was 'above the law.' DA Kratz told [her] that he would not have a problem if he was stopped while driving home because he had friends."

In the days that followed, Kratz continued to text her with unreleased information about the case, including the fact that investigators had discovered a body. That's when he invited her to the autopsy, "as long as she would wear heels and act as his girlfriend." According to the documents, she "stated that she thought this was wrong on so many levels." There was apparently no second date.

The woman's statement and the e-mails sent by Kratz can be found at the following link:

https://www.convolutedbrian.com/Support/kratz/DOJ_Investigation/Kratz_Records_Part_1_20110401102147362.pdf

Kratz's Pretrial Behavior Called 'Unethical' by Others within the Legal Community

By lmogier at Reddit

I came across this article that Zellner tweeted a link to recently and found it Interesting that even Kratz's peers/colleagues think his behavior was unethical and wrong (although he still defends his actions - cause he is THE PRIZE!)...

http://www.postcrescent.com/story/news/local/steven-avery/2016/01/15/kratzs-pretrial-behavior-called-unethical/78630248/

Some highlights:

-- "To me, those press conferences would suggest a colorable violation of the (bar association) trial publicity rule. The risks of prejudice are magnified in smaller communities because of the pervasive nature of the publicity and the likelihood that virtually the entire community will have strong feelings about the case. The Avery case appeared to have captured the attention of the Fox Valley market ... and you cannot un-ring that bell." ----Ben Kempinen, University of Wisconsin Law School clinical professor of law and director of the Prosecution Project.

Prosecutors are not supposed to be making public statements prior to a defendant's trial regarding the following areas:

"The character, credibility, reputation or criminal record of a party, suspect in a criminal investigation or witness, or the identity of a witness, or the expected testimony of a party or witness." "The identity or nature of physical evidence expected to be presented." "Any opinion as to the guilt or innocence of a defendant or suspect in a criminal case or proceeding that could result in deprivation of liberty." "Information the lawyer knows or reasonably should know is likely to be inadmissible evidence in a trial and would, if disclosed, create a substantial risk of prejudicing an impartial trial."

Abbe Smith, director of the criminal defense and prisoner advocacy clinic at Georgetown University, said Kratz's opening declaration in his March 2, 2006, press conference exclaiming "we now have determined" and his continuing comments about Dassey supposedly hearing screams and running over to his uncle's trailer were highly improper for a press briefing.

"It's unethical behavior with no legitimate purpose," Smith told USA TODAY NETWORK-Wisconsin. "Prosecutors should err on the side of not inflaming the public. To prosecute a case in the media damages the legal system because you're prejudicing the jury process."

*"There is absolutely no purpose for any of this stuff that Ken Kratz did," * said Ritnour, who served two terms in two largely rural counties similar to Manitowoc and Calumet counties, from 2003 through 2010.

"He likes and wants his name out there. He is definitely trying to get to the people who will then be in the jury pool. Even if Kratz loses (at trial), he still kind of wins anyway because he convicted Avery and Dassey in the court of public opinion."

However, several lawyers and courtroom experts said that Kratz's behavior was clearly inappropriate for any prosecutor because his statements were eroding the opportunity for Dassey and Avery to receive a fair and impartial jury trial.

FORENSIC EXPERT: KRATZ GIVES FALSE STORY.

Brent Turvey, a nationally recognized forensic scientist and criminal profiler in Alaska, said the crime scene evidence collected from inside of the Avery residence does not match up with Kratz's salacious and inflammatory press conference statements around the time of Dassey's arrest and purported confession to the pair of investigators.

Ken Kratz gives this false story," Turvey said. "It's pure fantasy. The entire theory comes from the fantasies of these police investigators (interviewing Dassey). The problem here is that (Kratz) gave false information, this whole sexual fantasy, talking about Teresa Halbach talking and begging and yelling when none of this had any forensic science to back it up.

"Why does this matter? Because you are not allowed to gin up the public and misrepresent the evidence when talking to the press, and the only reason you do that is when you and the police don't have a good case to begin with. Ken Kratz was trying this case in the press to disparage the defendants. What these judges should have done was put a gag order in place. There should have been some consequences from the Wisconsin Bar Association, and the judge who is seeing this nonsense go on should have put a stop to this. Nobody in this case wanted a fair trial."

Link to motion that lists ALL of publicity (and actual wording) of media coverage - including Kratz's:

http://www.stevenaverycase.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/01/Defendants-Memo-on-Examples-of-Prejudicial-Pretrial-Publicity.pdf

Sexual Misconduct Accusations Against ‘Making a Murderer’ Prosecutor Undermine Conviction, Defense Attorney Says

The Wisconsin prosecutor who convicted Steven Avery, the subject of the blockbuster documentary Making a Murderer, bragged about his role in the controversial case to impress women he wanted to date and was accused multiple times of abusing his official position to coerce women into sexual conversations and acts, according to documents obtained by Newsweek.

New and disturbing details about the accusations against prosecutor Ken Kratz emerged from a 143-page case file kept by the Wisconsin Department of Justice (DOJ) during its 2010 investigation of Kratz, who initially received glowing praise for his handling of the 2007 trial that convicted Avery of killing young photographer Teresa Halbach.

Kathleen Zellner, the defense attorney working to free Avery, tells Newsweek the allegations cast doubt on the conviction and are especially troubling given Kratz’s behavior in the lead-up to the trial.

Zellner draws a connection between the prosecutor’s alleged sexual misconduct and the graphic press conference he gave before the trial. As the press conference began, Kratz asked young viewers to stop watching, then described how a sweaty Avery had shackled Halbach naked and screaming to his bed and invited his teenage nephew, Brendan Dassey, to rape and kill her. (The sexual assault and kidnapping charges against Avery were dropped before trial and on Friday a federal judge overturned Dassey's conviction.)

“They dismissed the sexual assault charges against Avery, and there was absolutely no proof of it,” Zellner tells Newsweek. “When you see a fabrication of reality such as what was done in that press conference, you wonder where those ideas come from [and] what would motivate someone to make up such a graphic scenario.” Zellner adds that the description Kratz gave at the press conference seems to be “the product of someone’s dark and disturbed fantasy.”Other outlets have reviewed the allegations of Kratz's sexual misconduct—most notably the Associated Press, in a story that forced his 2010 resignation. The AP reported that Kratz sent sexual texts to a domestic violence victim and followed up with stories about additional allegations against the prosecutor. Now the documents obtained by Newsweek shed new light on the accusations, including the allegation that he left $75 for a woman after his threats scared her into performing oral sex on him. They also detail his many boasts to women about his role in the Avery case, along with the steps authorities took to make sure he couldn’t destroy evidence once he learned he was being investigated. (The DOJ eventually decided not to bring criminal charges against Kratz.)

Kratz responded to a 27-year-old woman’s Craigslist ad in 2010, texting her, “I will treat you nice,” according to an interview DOJ investigators conducted with the woman. “He texted, ‘Do you know who I am, I am Kenneth Kratz the guy who prosecuted Steven Avery,” states one investigation report.

Two other women also told DOJ investigators that Kratz, the Calumet County district attorney, brought up the Avery case as he tried to woo them. “Kratz [told] her he was the most notable prosecutor in Wisconsin history because of this case,” investigators wrote in one report of a woman Kratz met on Match.com in May 2010.

That woman, a domestic abuse victim, said Kratz initially offered to advocate on her behalf with the judge and district attorney handling her husband’s criminal case, as well as help write her victim impact statement. But that early support from Kratz, who was chairman of the state Crime Victims’ Rights Board at the time, allegedly morphed into aggressive sexual requests. “CI [confidential informant] said that based on Kratz’s behavior and his cumulative communications with her, she felt like Kratz expected her to go to bed and have sex with him for his assistance with her victim impact statement,” the report reads.

Another woman told investigators that after meeting Kratz on Match.com in December 2009 and having one dinner with him, he began texting her regularly. “If I didn’t answer his texts immediately, he would become insecure and question why I hadn’t responded and would attack me or my character,” the woman said in an email that is included in the DOJ case file. “He would remind me of who he was, how he had prosecuted the biggest case around here, and what a prize he was.”

Kratz tells Newsweek that all the accusations against him are unfounded, citing the fact that the DOJ decided not to bring any criminal charges against him. “They had nothing. They thought they were going to charge me with misconduct in office, but none of that was ever true,” he says. Asked about his alleged boasts to women about the Avery case, he claims he was simply describing what he did for a living. Regarding the graphic press conference, Kratz says in an email to Newsweek that he drew his description of the sexual assault directly from the criminal complaint against Avery’s nephew, and now he wishes he had simply filed the complaint and not spoken to the press about it.

Kratz maintains that campaigning politicians pushed the investigation of him, and that a DOJ press release that asked for information about his misconduct triggered the numerous complaints against him. “It’s hounded me here for at least six years now, and I suspect that with Making a Murderer second season, the film crew isn’t going to make me one of the heroes. So I can’t imagine this is going to change anytime soon.”

While many of the 15 women interviewed in the DOJ investigation complained that Kratz made sexual comments and tried to sleep with them, at least two women also accused the longtime prosecutor of using his position to manipulate them into physical contact.

A woman who met Kratz when he prosecuted her for shoplifting in 2006 said the prosecutor called her “out of the blue” in 2009, said he was getting a divorce and then came to her apartment, where he said in a threatening manner that he “knew everything about her” and “if she did not listen to him, he could get her ‘jammed up,’” according to an investigation report. “While Kratz was at [the woman’s] apartment, [he] said he ties women up, they listen to him, and he is in control. [The woman] stated that Kratz wanted her to engage in bondage with him. She said he instructed her to give him a ‘blow job,’ and she did.”

The woman said she felt disgusted with herself during the sexual act—like she was a “crack whore”—and that when Kratz left she “puked her brains out” and stayed in bed for about a week. She also told investigators that she had been raped when she was 16 years old, and “this feels a lot like it.” Kratz left $75 on the woman’s kitchen counter and later called and texted her 50 or 60 times, according to the report. When she ignored him, Kratz left messages saying “if she did not contact him back, she would hear from him. He told her he knew everything about her, and there would be repercussions,” the report states. “Kratz became angry about the money, stating that it was a lot of money and wanting it back.”

The documents obtained by Newsweek also reveal new details about the DOJ investigation into Kratz and the prosecutor’s reaction to it. Then-Governor James Doyle asked the DOJ Division of Criminal Investigation to probe Kratz just six days after the AP report about his sexting. When news of the investigation broke and Kratz resigned from his job that paid $105,000 per year, the acting Calumet County District Attorney unplugged Kratz’s computer and put evidence tape over the plug opening. And both investigators and Kratz’s successor appeared to be worried the disgraced prosecutor would sneak into his old office to destroy evidence. When the DOJ director of field operations asked whether Kratz had the keys to the DA’s office, the acting DA said Kratz had both keys and the door lock codes that permitted access to the entire office. But as precaution, the acting DA said, he changed the codes on the front door of the DA’s office.

The investigation reports in the case file obtained by Newsweek uncovered many unflattering details about Kratz, who received positive media attention after the Avery trial. “All the girls that Kratz hired to work in his office are young and pretty,” a social worker told investigators. Kratz also allegedly put his hand up the skirt of a domestic violence victim in 1999 when he was prosecuting her husband—taking a call from his girlfriend while he and the victim sat on the couch together—and tried to impress her by claiming he could help her get custody of her children, another woman told investigators.

After a six-month investigation, the DOJ decided it would not charge Kratz with any crime. Assistant Attorney General Thomas Storm explained why his office decided none of the allegations against Kratz warranted criminal action in a report. No sexual assault charges could be brought over the 1999 incident because it was consensual and outside the statute of limitations, Storm wrote, and charges should not be brought over the allegation Kratz coerced the shoplifter he prosecuted into oral sex because the state lacked corroborating evidence and the woman had prior convictions and documented mental illness. Complaints about Kratz’s misconduct in office—like the three women who said the prosecutor tried to use the power of his position to date them—were “inappropriate behavior” but don’t satisfy the elements required for criminal prosecution, the DOJ decided.

After leaving the DA’s office, Kratz began work as a defense attorney and has said he was addicted to sex and pain pills when he sent Van Groll texts like “I’m the attorney. I have the $350.000 house.... You may be the tall, young, hot nymph, but I am the prize!” The Wisconsin Supreme Court suspended his law license for four months and ordered him to pay $23,904 to cover the cost of his disciplinary proceeding. And when Making a Murderer came out last year, enraged viewers flooded the Yelp page for his law practice with death threats and comments like, “Scum of the Earth.... Burn in Hell!”

Meanwhile, defense attorney Zellner says Avery is innocent and she’ll overturn his conviction—and Kratz’s case—with new evidence. She tells Newsweek, “This evidence on Kratz certainly undermines confidence in the verdict.”

How Does it Feel Mr. Kratz?

Part of the problem is that Wisconsin Prosecutors have almost unlimited power to do wrong. Kratz would have gotten away yet again with his coercion and breaking of rules had not someone alerted an outside news agency. We must keep in mind that Kratz is not alone. Wisconsin rules for prosecutors encourage a disregard for fairness and honesty.

By Brian McCorkle, ConvolutedBrain.com

September 21, 2010

I have always felt the pile‑on techniques used by police and prosecutors are unfair. These techniques have been used to paint defendants with intent to blacken the defendant in the eyes of the public. Press conferences are given with little regard for truth. The attempts to undermine are not limited to the accused. The desire for notoriety leads police and prosecutors to make public disparaging statements about “persons of interest” and even people and businesses that are not involved with a crime. Neither police nor prosecution is hampered with any requirement that their statements be truthful. Any response by citizens attempting to defend themselves can be twisted by prosecutors to claim some kind of guilt.

Our legislators are a part of this mess. The lawmakers in Madison, Wisconsin have happily added laws to allow prosecutors to charge the same crime with several different law violations. Plus, these wise lawmakers have added surcharges upon surcharges so a person guilty of a very minor crime will find the fine for the crime is a minor part of the indebtedness that Republicans and Democrats alike have heaped upon defendants. Most victims of this type of ganging up are people who are too poor to hire a competent attorney for self‑defense.

Of course, Calumet County District Attorney Ken Kratz has been more than happy to partake in undermining the accused and others. In the Great Hilbert Sex Ring, he and his sidekick Calumet County Sheriff Gerald (Jerry) Pagel, gave news conferences to keep the public’s voyeurism stoked. I’m sure it was a disappointment to both when their claim of a potential ever widening sex ring did not bear fruit. Part of that campaign was to excessively charge one of the parties so Kratz could claim he nabbed a patriarch.

Both Kratz and Pagel were eager to make public claims about Steven Avery prior to his trial for the murder of Theresa Halbach. Kratz claimed that Avery would only grant interviews to reporters who had the general appearance of the victim was bogus. It was actually police and prosecutor who attempted to force news interviews upon Avery even after his attorneys directed the authorities to stop. And, Kratz wanted only news reporters with a physical resemblance to Halbach to perform the interviews. But, local news organizations were very happy to be used by the prosecution.

Kratz even claimed that Avery committed the crime because he wanted to return to prison. His authority was the nephew of Avery, Brendan Dassey. Dassey, a special education student was pressured by investigators to produce a motive for the murder so he guessed. That was good enough for Kratz.

Kratz went after Dassey because he was the alibi witness that could destroy the State’s case against Avery. Kratz stepped forward with claims based upon an uncorroborated confession by Dassey. Kratz held a televised news conference in which he gave gruesome details about the death of Halbach. Evidence has not supported the details and at Dassey’s trial, the State gave opening statements and closing statements which conflicted about timelines and facts.

Kratz and his cronies were very willing to convict this boy because of notoriety and convenience. To be fair, the defense attorneys involved presented a very poor defense. One of the defense attorneys actually spent time and resources to try to find evidence against Steven Avery rather that attempt a defense of Dassey. Kratz attempted to pile on even more damaging accusations at the trial of Dassey. He was thwarted when a star witness refused to perjure herself. Kratz’s investigators didn’t cook her testimony as much as they thought.

Now; Kratz is caught attempting to seduce a person who was the victim of a beating and strangulation. He thought he would get away with it. The Associated Press was informed of his behavior, and he was in the limelight. Kratz tried to play innocent.

Kratz sent suggestive text messages (sexting) to a victim he expected to be a witness in a prosecution. The witness was also the victim of the crime.

The Wisconsin Department of Justice has already whitewashed his misconduct. The Office of Lawyer Regulation had already turned by a claim of misbehavior placed by the young woman Kratz attempted to coerce. The State Department of Victim Services has stood mute. So, the official Wisconsin stance was that Kratz is OK. The victim is collateral damage.

But, all is not quiet. Victim’s organizations piled upon the prosecutor demanding his resignation. A Wisconsin legislator (and former judge) demanded his resignation. Newspaper editorials are demanding that Kratz resign. Governor James Doyle has stated that he is awaiting a valid citizen complaint against Kratz so he can look at the possibility of removal of Kratz from office. The Wisconsin Association of District Attorneys sent Kratz a letter demanding his resignation.

Despite the reticence of those in the Wisconsin justice system, overwhelming calls from the public are calling for resignation or ouster. I would prefer disbarment.

Kratz’s responses have been that there was nothing sexual, or his wooing was consensual. His messages show the contrary. He let the victim know that he was the District Attorney, and he had the power. Her physical attractiveness paled before his awesomeness. It is also apparent from his text messages that this was nothing new for him. The messages progressed from a kind of concern to demands.

At any rate, his claims of innocence, and harmlessness are not keeping the demands of his ouster at bay.

His latest attempt to slither out of this predicament is to place himself on indefinite medical leave. I suspect he will next attempt a medical resignation to try to avoid consequences for his actions.

It wasn’t too long ago that Kratz was the darling. Now the voices clamoring for his resignation or ouster are growing. The pile‑on is a result of his misbehavior. Unlike those whom he and those like him attempted to undermine with repeated public accusations, he is has skewered himself.

Tell me, District Attorney Ken Kratz. How does it feel? It won’t stop.

Calumet County Prosecutor Ken Kratz Tries to Bully a Reporter

By Brian McCorkle, ConvolutedBrain.com

November 16, 2010

The Appleton, WI, based newspaper, the Post~Crescent, released a recording of an attempted interview of Ken Kratz by an Associated Press (AP) reporter. On 15 September, 2010 Ryan Foley interviewed Kratz about his attempt to seduce a witness.

The matter is from October and November, 2009, when Calumet County District Attorney Kratz sent over twenty text messages to Stephanie Van Groll. The messages were an attempt to bully Van Groll into a sexual relationship and gained Kratz the title of the sexting prosecutor.

Van Groll was a witness and the victim in a strangulation trial. Kratz had suggested to Van Groll that he was considering reducing charges against the perpetrator. He started texting her to tell her that he wanted to be helpful.

After the text messages escalated in tone and demand, Van Groll reported the behavior to the Kaukauna, WI Police Department. The police referred the case to the Wisconsin Department of Justice (DOJ), headed by Attorney General JB Van Hollen. The DOJ whitewashed the incident.

Around September, 2010, someone tipped off the AP and that was the beginning of the end for Kratz. First, Kratz announced that he refused to resign. Governor Jim Doyle scheduled removal hearings and Kratz, who had self‑committed to a treatment program, resigned.

Van Hollen blamed others when it was his department that gave Kratz a sweetheart deal that included remaining silent. Kratz manipulated the process and was dishonest in his self‑reporting to other entities.

The recording shows that Kratz was fully expecting to continue manipulating the process and the reporter. He was not going to answer any questions. He wanted one answer and his posturing through the session was an attempt to obtain that answer.

Kratz wanted the name of the person who tipped the AP about the coverup at the Wisconsin Department of Justice. Ironically, Kratz was insistent that the information was leaked at the direction of Attorney General J.B. Van Hollen although, it was Van Hollen’s department that agreed with the proposals of Kratz at the time of the investigation in 2009.

Kratz began the interview by attempting to steer the reporter, Ryan Foley, away from the heart of the matter. Whenever Foley asked Kratz about the appropriateness of his attempt to seduce a witness, who was also a victim, Kratz stated he would not answer that.

Kratz wanted to know what the Office of Lawyer Regulation (OLR) said about the matter knowing full well that the OLR had not released the results of his self‑reporting. He gave the information to the OLR that had cleared him of wrongdoing. He did not state that the complaint to the OLR was a self‑report and that he was dishonest about the details.

Kratz continued attempts to have Foley reveal the source of the information. Kratz claimed that this was not news and that Foley was fed a story. Kratz attempted further manipulation of Foley, acting like the corrupt prosecutor that he was, “Let’s see how honest you’re going to be with me.” Then Kratz stated that the DOJ was behind an attempt to smear him.

Kratz continued doing most of the talking. Attempts by Foley to get Kratz to admit to inappropriate behaviors were stonewalled. The reporter was able to state that Kratz was the interviewee, not the interviewer. Foley stated that he had the police reports and the statement of the person Kratz attempted to victimize. Kratz responded by claiming the reporter was willingly being used. At one point Kratz claimed that Foley was on the payroll of someone who wanted Kratz ousted.

Kratz said he was the Chairman of the Crime Victims Rights Board (CVRB), but neglected to say that he had been forced to speak with the board about his behavior. Of course, he was not candid with the members of the board. He reluctantly resigned his chairmanship rather than fess up. Kratz claimed he wrote the law on Criminal Victims. He praised his past performances and said that this would be a terrible thing to print because he was such a great guy. He minimized his crime by saying that just a simple allegation can destroy a local prosecutor.

In 2006, Kratz had no problem making a televised performance when he gave an uncorroborated blow by blow description of how Brendan Dassey and Steven Avery had murdered Teresa Halbach. The whole point of Kratz going after Dassey was to remove an alibi witness from testifying in the Avery trial. The evidence that would have corroborated the Dassey confession was not found or not gathered. When it fit the goals of Kratz, he was all for making any statement that would help his own agenda. He had no problem in destroying Dassey to get a conviction.

At the end of the interview things became interesting. Earlier Kratz had mentioned Van Hollen as the person behind the leak. Kratz’ questioned, “What personally happened to between Ken and JB Van Hollen? Do you know the history? Do you know why JB Van Hollen wants this run?”

I would like to know what specifically Kratz had in mind when he insisted that Van Hollen was after him. Obviously, Van Hollen was willing to cover the mess up. The Wisconsin Justice Department allowed Kratz to dictate the terms for the resolution of his illegal behavior. Van Hollen allowed Kratz to self‑report to the OLR with no oversight. Of course, Kratz gave a report that minimized his behavior and intimated that his victim was a willing participant and reported because her mother made her do so.

Kratz’s bad acts go well beyond this case that finally was made public. His conniving goes well beyond attempted coercing people into sex with him. But, I don’t see Van Hollen taking a close look at the history of Ken Kratz. Van Hollen would rather the innocent sit in prison and perpetrators go free.

Kratz is not the only prosecutor in Wisconsin who runs wild. That needs to be addressed by the Wisconsin Legislature.

Court Documents Contain Information Regarding Rape Committed by Kratz

November 16, 2010

The Appleton, WI, based newspaper, the Post~Crescent, released a recording of an attempted interview of Ken Kratz by an Associated Press (AP) reporter. On 15 September, 2010 Ryan Foley interviewed Kratz about his attempt to seduce a witness.

The matter is from October and November, 2009, when Calumet County District Attorney Kratz sent over twenty text messages to Stephanie Van Groll. The messages were an attempt to bully Van Groll into a sexual relationship and gained Kratz the title of the sexting prosecutor.

Van Groll was a witness and the victim in a strangulation trial. Kratz had suggested to Van Groll that he was considering reducing charges against the perpetrator. He started texting her to tell her that he wanted to be helpful.

After the text messages escalated in tone and demand, Van Groll reported the behavior to the Kaukauna, WI Police Department. The police referred the case to the Wisconsin Department of Justice (DOJ), headed by Attorney General JB Van Hollen. The DOJ whitewashed the incident.

Around September, 2010, someone tipped off the AP and that was the beginning of the end for Kratz. First, Kratz announced that he refused to resign. Governor Jim Doyle scheduled removal hearings and Kratz, who had self‑committed to a treatment program, resigned.

Van Hollen blamed others when it was his department that gave Kratz a sweetheart deal that included remaining silent. Kratz manipulated the process and was dishonest in his self‑reporting to other entities.

The recording shows that Kratz was fully expecting to continue manipulating the process and the reporter. He was not going to answer any questions. He wanted one answer and his posturing through the session was an attempt to obtain that answer.

Kratz wanted the name of the person who tipped the AP about the coverup at the Wisconsin Department of Justice. Ironically, Kratz was insistent that the information was leaked at the direction of Attorney General J.B. Van Hollen although, it was Van Hollen’s department that agreed with the proposals of Kratz at the time of the investigation in 2009.

Kratz began the interview by attempting to steer the reporter, Ryan Foley, away from the heart of the matter. Whenever Foley asked Kratz about the appropriateness of his attempt to seduce a witness, who was also a victim, Kratz stated he would not answer that.

Kratz wanted to know what the Office of Lawyer Regulation (OLR) said about the matter knowing full well that the OLR had not released the results of his self‑reporting. He gave the information to the OLR that had cleared him of wrongdoing. He did not state that the complaint to the OLR was a self‑report and that he was dishonest about the details.

Kratz continued attempts to have Foley reveal the source of the information. Kratz claimed that this was not news and that Foley was fed a story. Kratz attempted further manipulation of Foley, acting like the corrupt prosecutor that he was, “Let’s see how honest you’re going to be with me.” Then Kratz stated that the DOJ was behind an attempt to smear him.

Kratz continued doing most of the talking. Attempts by Foley to get Kratz to admit to inappropriate behaviors were stonewalled. The reporter was able to state that Kratz was the interviewee, not the interviewer. Foley stated that he had the police reports and the statement of the person Kratz attempted to victimize. Kratz responded by claiming the reporter was willingly being used. At one point Kratz claimed that Foley was on the payroll of someone who wanted Kratz ousted.

Kratz said he was the Chairman of the Crime Victims Rights Board (CVRB), but neglected to say that he had been forced to speak with the board about his behavior. Of course, he was not candid with the members of the board. He reluctantly resigned his chairmanship rather than fess up. Kratz claimed he wrote the law on Criminal Victims. He praised his past performances and said that this would be a terrible thing to print because he was such a great guy. He minimized his crime by saying that just a simple allegation can destroy a local prosecutor.

In 2006, Kratz had no problem making a televised performance when he gave an uncorroborated blow by blow description of how Brendan Dassey and Steven Avery had murdered Teresa Halbach. The whole point of Kratz going after Dassey was to remove an alibi witness from testifying in the Avery trial. The evidence that would have corroborated the Dassey confession was not found or not gathered. When it fit the goals of Kratz, he was all for making any statement that would help his own agenda. He had no problem in destroying Dassey to get a conviction.

At the end of the interview things became interesting. Earlier Kratz had mentioned Van Hollen as the person behind the leak. Kratz’ questioned, “What personally happened to between Ken and JB Van Hollen? Do you know the history? Do you know why JB Van Hollen wants this run?”

I would like to know what specifically Kratz had in mind when he insisted that Van Hollen was after him. Obviously, Van Hollen was willing to cover the mess up. The Wisconsin Justice Department allowed Kratz to dictate the terms for the resolution of his illegal behavior. Van Hollen allowed Kratz to self‑report to the OLR with no oversight. Of course, Kratz gave a report that minimized his behavior and intimated that his victim was a willing participant and reported because her mother made her do so.

Kratz’s bad acts go well beyond this case that finally was made public. His conniving goes well beyond attempted coercing people into sex with him. But, I don’t see Van Hollen taking a close look at the history of Ken Kratz. Van Hollen would rather the innocent sit in prison and perpetrators go free.

Kratz is not the only prosecutor in Wisconsin who runs wild. That needs to be addressed by the Wisconsin Legislature.

Court Documents Contain Information Regarding Rape Committed by Kratz

Ken Kratz Scandal Links at ConvolutedBrian.com

Emails between Ken Kratz and Wisconsin Department of Justice

Self-report to Wisconsin Office of Lawyer Responsibility

Ryan Foley interview of Ken Kratz

Disciplinary Complaint by Office of Lawyer Regulation

Disciplary complaint by Office of Lawyer Regulation

Wisconsin Department of Justice Documents and Findings

DOJ Investigation part 1

DOJ Investigation part 2

DOJ Investigation part 3

DOJ Investigation part 4

DOJ Investigation part 5

DOJ Investigation part 6

DOJ Investigation part 7

Scott Hassett, Candidate for Attorney General, Critique of AG John Byron Van Hollen's Handling of the Scandal

Critique of Wisconsin DOJ handling of Kratz case

Graphic saved on Ken Kratz's office computer as Calumet County District Attorney: Attorney General John Byron Vanhollen is also "Most Worshipful Grand Master" of Wisconsin Masons

Press Release by Wisconsin Crime Victims Rights Board

Press release by Wisconsin Crime Victims Rights Board

Wisconsin DOJ does not file criminal charges against Former Calumet County District Attorney Kenneth Kratz

Press Release from Ken Kratz

2009 Conference on Crimes Against Women

Tom Fassbender, Norm Gahn, Ken Kratz and Mark Wiegert are featured presenters (pp. 9, 10). It is not clear who paid for transportation and lodging or if these four received a fee.

Brochure, 2009 Conference on Crimes Against Women

Ken Kratz Scandal - Documents from 2010

https://www.reddit.com/r/TickTockManitowoc/comments/5vrdyl/ive_been_reading_the_k_kratz_scandal_documents/

Discussion by Media

http://host.madison.com/wsj/news/local/crime_and_courts/disgraced-former-da-kratz-cited-by-regulators-for-alleged-sexual/article_4602156e-236a-11e1-b8b2-001871e3ce6c.html

Kratz Computer Forensic Reports

https://www.reddit.com/r/TickTockManitowoc/comments/7k5793/kratzs_computer_forensic_reports_online/

Self-report to Wisconsin Office of Lawyer Responsibility

Ryan Foley interview of Ken Kratz

Disciplinary Complaint by Office of Lawyer Regulation

Disciplary complaint by Office of Lawyer Regulation

Wisconsin Department of Justice Documents and Findings

DOJ Investigation part 1

DOJ Investigation part 2

DOJ Investigation part 3

DOJ Investigation part 4

DOJ Investigation part 5

DOJ Investigation part 6

DOJ Investigation part 7

Scott Hassett, Candidate for Attorney General, Critique of AG John Byron Van Hollen's Handling of the Scandal

Critique of Wisconsin DOJ handling of Kratz case

Graphic saved on Ken Kratz's office computer as Calumet County District Attorney: Attorney General John Byron Vanhollen is also "Most Worshipful Grand Master" of Wisconsin Masons

Press Release by Wisconsin Crime Victims Rights Board

Press release by Wisconsin Crime Victims Rights Board

Wisconsin DOJ does not file criminal charges against Former Calumet County District Attorney Kenneth Kratz

Press Release from Ken Kratz

2009 Conference on Crimes Against Women

Tom Fassbender, Norm Gahn, Ken Kratz and Mark Wiegert are featured presenters (pp. 9, 10). It is not clear who paid for transportation and lodging or if these four received a fee.

Brochure, 2009 Conference on Crimes Against Women

Ken Kratz Scandal - Documents from 2010

https://www.reddit.com/r/TickTockManitowoc/comments/5vrdyl/ive_been_reading_the_k_kratz_scandal_documents/

Discussion by Media

http://host.madison.com/wsj/news/local/crime_and_courts/disgraced-former-da-kratz-cited-by-regulators-for-alleged-sexual/article_4602156e-236a-11e1-b8b2-001871e3ce6c.html

Kratz Computer Forensic Reports

https://www.reddit.com/r/TickTockManitowoc/comments/7k5793/kratzs_computer_forensic_reports_online/

[–]Classic_Griswald 0 points 1 day ago

ReplyDeleteIt was stated or alleged elsewhere some of the stuff MA recounted happened to her by someone else.

Consider the fact that Wendy Baldwin threatened her for her most damning statements against Avery. Consider the fact that Wendy Baldwin took her to her own house, to do the interview. Consider the fact that Candy (MA's mom) doesn't like SA, and she is friends with Colborn.

If MA is truly a victim, Id really like to know why Baldwin had to/was willing to threaten her. Even if she is, this is not how police should be treating someone like that.

It's hard to believe the victimhood of the people who make allegations against Avery when the common theme is-1 allegations are not made until there is a falling out. 2-MTSO or CASO agents threaten or coerce them into making statements. 3-the claims themselves are inconsistent.

[–]Classic_Griswald 4 points 1 day ago*

You obviously haven't read the DOJ files on Ken Kratz. He had over a dozen victims come forward, one of which stated he had forced sex with her. Even the OLR report cites it as forced sex.

There were also sex crimes alleged against him that dated back to the late 80s, but statute of limitations prevented him from being prosecuted.

The rape case against him recently was not prosecuted because the witness was deemed 'unreliable' because she had a criminal history (which Kratz himself prosecuted), a drug history and mental issues.

Ironically, Kratz himself had a drug problem at the time, he had mental issues NPD, and his criminal history was being subverted when he was covering up his crimes, he managed successfully for a year, berating, demeaning, disparaging the investigators from DOJ, envying cronyism and threatening them while they investigated his crimes.

You're comparing KK sexting someone he shouldn't have with SA beating, raping, and abusing women in escalating behaviour...

Actually, the real problem is that KK and others like him are responsible for the alleged cases against Avery. How do you trust the people writing the reports when they themselves are covering up their own crimes?

So instead you take any accusation against Avery as gospel, but ignore the accusations against Kratz et al, who are documented covering up their own crimes.

You don't see the irony here? Please show us emails of Avery threatening and demeaning the investigators looking into his actions. You wont. You will find a whole bunch of files making plenty of claims against Avery, but then.... not prosecuted. Why is that?

For Kratz and his buddies though, we can show you where he was covering up his allegations, threatening investigators for even looking into the crimes, and then getting off these legal challenges by utilizing his position.

So you have Avery, well hated (possibly something to do with his uncle being a top cop back in the day, who Kocourek worked under), and a dozen or so investigations on Avery, but no formal charges. All of the allegations against Avery seem to be in similar nature, from very specific people, with very specific people investigating and trying to bring legal action against him. e.g. Claims by MA, derived from Candy, who doesn't like Avery. Baldwin investigates. Baldwin even threatened MA, supposedly a victim. Similar to threatening Jodi. So the common theme here is threaten Avery's ex's or people close to them, get dirt on him, try to prosecute.

Then you have Kratz, who utilizes his position to prevent charges from happening at all. Random women from all walks of life come forward, to lob their accusations against Kratz, because they feel he is a predator. No one has to be threatened or harassed. Women come forward because they are afraid of the damage he is causing.

The (Intentional) Forgetful Kratz List (self.TickTockManitowoc)

ReplyDeletesubmitted by GiltyMe at Reddit on June 3, 2016

In regards to /mae-mays recent (and great) post about the Zander Road sign, Kratz told the jury that they would be hearing more about this location but then no other follow up was done.

So let's create a list of all the things that he told the jury that he would be following up on but never did.

[–]Canuck64 13 points 9 hours ago

Not quite intentionally forgetful, instead intentionally avoiding.

[–]MTLost 5 points 7 hours ago

Do you think this was a tactic with him? Mention something and say he will circle back to it later in a way that seems very important and pertinent, but "forget" to go back and actually do it? Seemed to work great, because people were under the impression that these were facts even though he never really proved anything at all.

Super Sneaky, in my opinion, and I think he did this very deliberately as a smoke and mirrors thing because he knew he couldn't substantiate his story. If he had actually gone back to prove his point by calling the witnesses or discussing findings, it would be obvious that his story lacked substance or even worse, the defense could expose the holes in the case very directly and openly.

Instead, he avoided any contradictions by planting the thought and letting it go - leaving that seed to grow into something more than it was.

He is actually a very smart person, underneath all that smarminess, bluster, sweat and puffing - just imagine what he could have accomplished if he had put his super powers to use fighting for Justice instead of Evil.

[–]uk150 4 points 7 hours ago

It's very strange that he forgot anything. He had a 'to do' list in front of him. A list that he annoyingly ticked every time every time the gobshite asked a question.

https://www.reddit.com/r/TickTockManitowoc/comments/4mc82c/the_intentional_forgetful_kratz_list/

I think my MAM er, obsession, got me booted off a jury! (self.TickTockManitowoc)

ReplyDeletesubmitted by GeorgeMarvin

Recently I reported for jury duty - I think for the 5th time in my life. It never comes at a convenient time, but I have always appreciated the experience once I let go of those other plans. I always feel very proud of my country after I participate in a jury. Anyway, this time I was the first juror listed for several grand jury cases, so I knew I would get called. Sure enough, I do along with 18 others, and we sit down to begin answering the prosecutors questions. The case involved a man accused of prostitution. The man claimed police entrapped him. The prosecutor finished his questions and the defense attorney begins to question us. Again, usual questions about job, past experiences with various types of crime, etc.

Next, she asks how many people watch crime shows like NCIS, etc. Why do we like them, etc. She follows that up with "Who has watched MAM?" I was the only one to raise my hand. She seemed as surprised as I that no one else had watched it. She asked me to summarize the show, and I enthusiastically launched in. I know all the names, the dates, the ins, the outs, and I realize that this is probably not going to endear me to the prosecution. Just like that, I am off the jury and free to return to r/TickTockManitowoc.

[–]Redditidiot1 13 points an hour ago

They don't want people that know the system well. Its a sad state of jury selection. You can't appear too knowledgeable about the behind the scenes magic show.

[–]MamaTried1981 7 points an hour ago

There was a trial going on in my state back in January where the article in the paper said the jury was instructed NOT to watch MaM during the trial.

I thought that was really odd, until I read another article about the same trial and I realized that O'Kelly was an "expert" witness for the prosecution. They decided to keep him as a witness even after the release of MaM because the state had already paid him an outrageous amount of money for his "services."

[–]MamaTried1981 4 points an hour ago

I googled because I couldn't remember the exact details, and apparently the state didn't pay him, so he raised the bill to $37,000! Ha!

http://www.freep.com/story/news/local/michigan/macomb/2016/04/25/cell-phone-expert-bill-vancallis/83503812/

[–]MustangGal 3 points an hour ago

Love it. :) I need to tell my daughter this, she just got her letter for next month.

[–]anditurnedaround 3 points an hour ago

I wonder why she asked you to summarize? To see what side you were on? If yes, why would she have you give her the answer she would need and also let the prosecution know at the same time they would want you out. (I am assuming you believe in corruption with this statement??)

I would think she would be more subtle? Especially since you could be her best juror depending on how you felt.

Kinda neat she asked you about your passion though! Sorry you missed out on your service because you're knowledgeable :(

[–]7-pairs-of-panties 2 points an hour ago

If you wanna be on a jury you gotta play kinda dumb, yet an upstanding citizen w/o too many of your own opinions on things. Than they'll pick you.

https://www.reddit.com/r/TickTockManitowoc/comments/4urmzm/i_think_my_mam_er_obsession_got_me_booted_off_a/

[–]smash-_- [score hidden] 27 minutes ago*

ReplyDeleteMake no mistakes, KK was in on this. He knew what was planted, and made others (SC/Eisenberg/FBI) ensure that the planted evidence stood up in court. He also fabricated evidence himself (phone records), and stood behind the coercion of a mentally challenged child. KK never worked for the victim, or for justice. He worked for the crooked cops and dragged down the good cops along the way.

In my opinion, himself and Willis should be held accountable to the highest level over the misconduct that occurred and the injustice brought with it. scumbags!

[–]dark-dare [score hidden] 5 minutes ago

He was on the scene before he was named prosecutor even, he was in on it from the start. That being said, they totally knew what type of person he was and used him, played him like a fiddle. A ethical prosecutor would not have taken this case. They set KK up like they did everyone else. But I do NOT feel sorry for him in the least.

[–]blondze [score hidden] 17 minutes ago

of course he knows, he's known all along and didn't care. Thats how most prosecutors work- what they get paid for has nothing to do with truth, they get paid for getting convictions. This particular prosecutor has further proven himself to be a slimeball of the worst kind with his sexting creepiness. The Avery case isn't a one time deliberate set up,it's KKs mode of operation. Averys case is most likely just one of many;we only know about it because of the mam doc. And that makes me think that anyone who has ever been convicted by him did not have a fair trial. They didn't even a chance.

[–]Refukulator 5 points an hour ago

Kratz was hopped up on goofballs and Brandy Old Fasioned chasers, he was blinded by his own self-induced haze.

The Sweaty One's day is coming, he can run but he can't hide.

Like a cornered rat. A big, fat, sweaty rat.

[–]ziggymissy [score hidden] 32 minutes ago

It's even in his name: kRATz.

https://www.reddit.com/r/TickTockManitowoc/comments/4zux45/kk_definitely_knows/

Ken Kratz was Bashed on Yelp

ReplyDeleteA week after the doc aired, doc fans took to Yelp to warn potential new clients checking his law practice’s Yelp page against hiring him.

“Mr. Kratz is a seasoned sexual harasser, with deep knowledge of abuse victims which he took advantage of. He has a long experience in evidence fabrication, and has the required strategic thought skills to send innocent men to jail for forged crimes,” one man wrote in a Yelpreview posted Sunday. “When you think of garbage think of Mr. Kratz, he is the living representation of immorality and indecency that you need by your side to solve any legal issues.”

KEN KRATZ QUOTES:

ReplyDelete"No text yet today? I’m feeling ignored. Are you even up yet?"

"I know this is wrong. I am such an honest guy, and straight shooter…but I have to know more about you… Are you the kind of girl that likes secret contact with an older married elected DA…the riskier the better?"

"Still wondering if I’m worth it? Can I help you answer any questions?"

“Why would such a successful, respected attorney be acting like he’s in 7th grade? Are you worried about me?”

"You should never lie to me! Obviously we have talents and this to offer that the other is intrigued by [sic], or you would have called me creepy. You wanna accept."

"It would go slow enough for Shannon’s case to get done. Remember it would be special enough to risk all,"

"Hey..Miss Communication, what’s the sticking point? Your low-self esteem and you fear you can’t play in my big sandbox?[sic]

"You may look good at first glance, but women that are blonde, 6ft tall, legs and great bodies don’t like to be shown off or to please their men! [sic]"

"I’m the atty. I have the $350,000 house. I have the 6-figure career. You may be the tall, young, hot nymph, but I am the prize."

"I would not expect you to be the other woman," "I would want you to be so hot and treat me so well that you’d be THE woman! R U that good?"

[–]JBamers 12 points 1 day ago

ReplyDeleteYes! He is a predator and just like paedophiles groom their victims, he was choosing the weakest women he could find and using his power as DA to have his way with them. He's an utter sicko!

[–]DarthLurker 17 points 2 days ago

He is blaming this behavior on pain pills... but pain pills don't make you a sexual deviant, in fact just the opposite effect is observed.

According to studies, opioids whose brand names include Vicodin, Percocet, and OxyContin— can lower testosterone levels, suppress sexual function in men, and cause erectile dysfunction. They can also contribute to low libido and difficulty with orgasm in both sexes.

Suprise, KK is playing the victim card when in fact he was always the predator.

[–]Machinato 1 point 1 day ago

Kratz appears to have used the NPD stuff via a therapist in order to escape a criminal charge and how he's back all over the TV which he previously claimed I think was driven by NPD and the stress in turn led to his pain killer addiction, so he must now be claiming he's cured but just has to go all over TV again to correct all the wrongs or something on behalf of the victims I guess, what a fraud.

[–]MTLost 8 points 1 day ago

http://i.imgur.com/2qU0tqZ.png

https://www.convolutedbrian.com/ken-kratz-scandal-links.html

The accusations are astonishing. There were so many of them, and this keeps getting generalized as if he were only caught sexting one person, which he excuses as if intentions were misunderstood. Dig into it and find out that more than 15 victims came forward to testify with their experiences, all very detailed, very similar and very twisted. And those were only the ones who spoke up, bet there were more.

I discovered this last year, when reading his aggressive emails when he confronted those who dared investigate him. His tone and language was aggressive and entitled, and there was not a spit of remorse. The drugs and personality disorder where his way to try to put victim spin on his behavior, again, simply excuses to try to get out of punishment.

He should have been brought up on criminal charges, not simply sanctions based on his role as an attorney.

[–]denmanstace 5 points 1 day ago

Piece of (#$%...that what this guy is...even more so now...and more of a suspect in my mind too...I had always thought of him as a two bit puppeteer...drunk on his own blood, but now, my mind goes..."why not? why can't he be the killer...what was his alibi?"

[–]PetrichorGirl 4 points 1 day ago

I agree. And if we accept the theory that LE/the state killed TH, KK becomes an even more plausible suspect. Who better to arrange the killing than the person who would later orchestrate all the evidence against SA?

https://www.reddit.com/r/TickTockManitowoc/comments/5vrdyl/ive_been_reading_the_k_kratz_scandal_documents/

"Ken Kratz conflates and distorts his cherry picked evidence and presents a story a hollywood horror film producer would find contrived." - magilla39, Reddit

ReplyDeleteDetailed Review of Kratz's Book: Claims vs. Facts and Other Observations (self.TickTockManitowoc)

submitted 3 days ago * by Nexious - announcement

https://www.reddit.com/r/TickTockManitowoc/comments/5vk526/detailed_review_of_kratzs_book_claims_vs_facts/

Kratz - The Real Truth Behind His Book Of Lies

February 23 at 6:23pm ·

Many of you will be aware of the name ‘Ken Kratz’ from the ‘Making A Murderer’ documentary series that was aired on Netflix. To some he will just be that District Attorney with a high pitched feminine voice that worked hard to find Steven Avery, and Brendan Dassey guilty. To others, that looked more deeply in to the case, he will be perhaps remembered as the sleazy former DA that was involved in a ‘sexting’ scandal and lost his job and marriage due to his many ‘indiscretions’.

However, to people that have looked even further in to his ‘sexting’ scandal (than just the few media articles and news reports that covered it at the time) and the Avery and Dassey cases as a whole, he is a man of deeply immoral practices in his personal life and his professional life, especially as someone who worked in a public service role of truth and honestly.

To those of you who want to see all the information about Kenny K and his questionable past please read all of the official documents listed here; https://www.convolutedbrian.com/ken-kratz-scandal-links.html

The purpose of this Facebook Page is not to try and destroy the reputation of Ken Kratz (he has done that himself), the purpose is to prove that the book he has written on the Steven Avery case is not only full of just his biased opinions stated as fact, but also outright lies - that official court transcripts, police reports, other documents and interviews will show.

The posts following this one will list the lies and unproven opinions passed as facts in Ken’s book (with the page number) and we will show what the actual truth is, via official documents and records. And in turn expose Kratz’s Alternative Facts.

This page, and the information provided, has been created with the help of dedicated people investing days, weeks and months of research. Most of them on the Tick Tock Manitowoc Reddit community; https://www.reddit.com/r/TickTockManitowoc/ as well as truth seeking people from all over the world on Twitter, Facebook and various websites, including professional journalists who have taken the time to look in to the Avery and Dassey cases further. Individual contributors will be thanked and acknowledged accordingly.

Ken Kratz is currently trying to cash in on Teresa Halbach’s murder by whoring his book to every TV and Radio station that will have him on, even though he knows it contains lies. Regardless of whether you think Steven Avery and Brendan Dassey are guilty or innocent, you have the right to read truthful information and not a work of fiction.

https://www.facebook.com/KratzsAlternativeFacts/#

[–]foghaze

ReplyDeleteThe narrative Kratz made up on how Teresa was murdered was his very own perversion!

https://www.reddit.com/r/TickTockManitowoc/comments/5vlum6/the_narrative_kratz_made_up_on_how_teresa_was/

[–]hos_gotta_eat_too 2 points 1 day ago

boom!

http://imgur.com/a/Ap9lW

[–]schmuck_next_door 3 points 2 days ago

I think Kratz forgot something... He forgot laying on the couch and eating Corndogs!

Everything this guy touches or says has sexual overtones! I'll betcha he has lots and lots of practice with those corndogs!

http://imgur.com/wu6qtJE

more at:

https://www.convolutedbrian.com/ken-kratz-scandal-links.html

[–]roblopes 5 points 2 days ago

The pot calling the kettle black: "It is bizarre," Kratz said. "There were dozens of sexual encounters that were described." - KK in the Hilbert Sex Ring case

Source: http://journaltimes.com/news/state-and-regional/five-charged-in-alleged-sex-ring/article_4f385db9-9253-5fb1-95d4-98ac4dda4887.html

[–]hos_gotta_eat_too 4 points 1 day ago

I tweeted the accusations link to his publisher and his new PR service with congrats on who they promote.

Also, tweeted Kenny himself, to tell him to make sure to watch 48 Hours on Saturday, as it should be a good one (special 2 hour episode on stalking)...

Page 12 or 13

Source: https://www.convolutedbrian.com/Support/kratz/DOJ_Investigation/Kratz_Records_Part_4_20110401102726569.pdf

[–]PicksyK 1 point 1 day ago

I'm sure if you googled that you found this blog?

http://fromwhisperstor.fr.yuku.com/topic/22752/Steven-Avery-Murder-Trial-John-Lees-Trial-Blog#.WK9X3es8KrU

Personally haven't seen this one. Interesting read but haven't gotten to the search hit about Hilbert yet.

[–]JJacks61 2 points 1 day ago

A quick search revealed nothing much one way or another. I did find an article that is fairly long but I'll leave a link in case anyone wants to read it. LINK