Making a Murderer Update: Brendan Dassey Release BLOCKED (Brad Schimel & Judges EXPOSED)

In fact, while actual innocence can help an inmate clear some of ADEPA’s procedural hurdles, it does not in and of itself entitle a petitioner to relief.

The legal system’s deference to finality is particularly troubling as we increasingly become aware of the prevalence of wrongful convictions.

DNA testing has taught us that sometimes – more often that we would like to admit – the criminal justice system gets things wrong. Innocent people get convicted. Unfortunately most wrongful convictions cannot be cured by DNA evidence.

Criminal defendants are wrongly convicted based on mistaken identifications, junk science, lying witnesses and, yes, false confessions.

While some wrongful convictions are overturned, most are not.

It is undeniable that the need for finality in criminal convictions is legitimate, even important. But so too is the need for justice and fairness. It is heartbreaking to think that even one person would wrongly spend his life in prison for a crime he did not commit. There is wisdom in what Benjamin Franklin once said: “It is better 100 guilty Persons should escape than that one innocent Person should suffer.”

Our system fails us all when it favors archaic rules and obscure technicalities over truth.

The press evince justifiable pride these days over so much great work—on sexual harassment,

Donald Trump and myriad other topics. For sure, it's mixed with anxiety over shaky business models, a Trump-fueled decline in public esteem and painful screw-ups, such as those of late by CNN and ABC News.

And then there's this frequent occupational reality: press achievements that come crashing or go unacknowledged. Those limits of journalism are typified by an engrossing and controversial Netflix series and its account of a troubled young man named Brendan Dassey.

On Friday a federal appeals court in Chicago released a rather

astonishing 4-3 decision in which it overturned a lower court and upheld a murder conviction against Dassey, a learning disabled Wisconsin man who was badgered by cops (at age 16) into a murder confession. The interrogation video was a central element of the Netflix series,

Making a Murderer, an exploration of apparent police and prosecutorial misconduct that got tons of attention after it premiered on Dec. 18, 2015. Here's a Rolling Stone

piece, one of many.

As much anger and conflict as the 10-part series generated about the conviction of the central figure, Steven Avery, there was virtual consensus that his nephew, Dassey, was screwed.

Even the reviews that underscored ambiguity about the whole Netflix project,

such as in The New Yorker, were taken aback by Dassey's fate. The New Yorker, for one, tagged him "a stone-quiet, profoundly naïve, learning-disabled teen-ager with no prior criminal record, who is interrogated four times without his lawyer present. In the course of those interrogations, the boy, who earlier claimed to have no knowledge of (the murder victim), gradually describes an increasingly lurid torture scene that culminates in her murder by gunshot. The gun comes up only after investigators prod Dassey to describe what happened to (the victim's) head."

So he was indicted and convicted. It was upheld in state court, then moved to federal courts where it was reversed. Now the entire appeals court decides the confession was legitimate and upholds a life sentence. Even the majority opinion, written by Indiana moderate David Hamilton (President Obama's first judicial appointee, in 2009), concedes, "He was young. He was alone with the police. He was somewhat limited intellectually. The officers’ questioning included general assurances of leniency if he told the truth, and Dassey may have believed they promised more than they did."

In fact, his I.Q. was 83. And he plaintively asked if he be back at school by 1:29 because he had a project due for 6th period.

But in what could be part of law school class on the profound criminal justice issues, notably confessions, Hamilton says he looks guilty. Those who concur are law and order conservatives Frank Easterbrook, Michael Kanne and Diane Sykes, who was briefly a Milwaukee Journal reporter before heading into the law. She was considered by Trump for the Supreme Court vacancy he filled with Neil Gorsuch, and her-ex husband, Charlie Sykes, is a longtime conservative radio talk host (and Trump critic from the right).

The majority take prompts two rather astonishing dissents by one or more of three judges: Diane Wood (who was always on Obama's short list for the Supreme Court), Ann Williams (a Ronald Reagan appointee who was the first black female on the Chicago federal bench) and Ilana Rovner (a Reagan appointee and saint of a person who escaped the Nazis in her native Latvia as a child with her mother).

Here's Wood: "His confession was coerced, and thus it should not have been admitted into evidence. And even if we were to overlook the coercion, the confession is so riddled with input from the police that its use violates due process. Dassey will spend the rest of his life in prison because of the injustice this court has decided to leave unredressed. I respectfully dissent."

And Rovner: "He was young, of low intellect, manipulable, without a friendly adult, and faced repeated accusations, deception, fabricated evidence, implic‐ it and explicit promises of leniency, police officers disingenuously assuming the role of father figure, and assurances that it was not his fault...Even under our current, anachronistic under‐ standing of coercion, Dassey’s confession was so obviously and transparently coercively obtained that it is unreasonable to have found otherwise."

It's ironic—maybe more—that Richard Posner, who was generally conceded to be the most influential judge-academic of his generation and the most influential judge not on the Supreme Court, suddenly and surprisingly quit the Chicago appeals court in September at a still prolific 78. If he were around, odds are that he would have voted with the dissenters, made it 4-4 and thus affirmed the earlier reversal of Dassey's conviction.

But no. Dassey will remain in prison, it would appear, until he dies. So you've got time to download

Making a Murderer. And, as you watch, be reminded of the strengths of journalism—but how even the most meticulously detailed conclusions can lead ultimately to exasperation, not satisfaction, and precious little attention.

By Michael C. Dorf, Newsweek

December 15, 2017

This article first appeared on Dorf on Law.

In 1970, the University of Chicago Law Review published an

article titled Is Innocence Irrelevant? Collateral Attack on Criminal Judgments

by federal appeals court judge Henry Friendly.

Judge Friendly was a judicial conservative in the small-c

sense, non-ideological, committed to deciding cases narrowly, and an expert

legal craftsman.

As a young lawyer, Chief Justice John Roberts clerked for

Friendly during Friendly's later years, and Roberts is fond of quoting (though

not always abiding by) Friendly's aphorism that if it is not necessary to

decide an issue to decide a case, it is necessary not to decide the issue.

Is Innocence Irrelevant? Was somewhat uncharacteristic of

Friendly in that it offered a controversial policy proposal on a politically

contentious issue.

Writing in a period of transition from the Warren Court to

the Burger Court, Friendly lamented that federal habeas corpus petitions by

prisoners sentenced under state law were too often succeeding based on

procedural irregularities that had no connection to innocence.

To use the more nakedly political argot, federal courts were

letting guilty state prisoners off on technicalities.

Quoting Justice Hugo Black's dissent in a

then-recently-decided case, Judge Friendly offered what he regarded—and what

many still regard—as a self-evidently sensible proposition: "The

defendant's guilt or innocence is at least one of the vital considerations in

determining whether collateral relief should be available to a convicted

defendant."

The ensuing nearly five decades have proven Judge Friendly

prophetic—but probably not in a way that he would have approved.

In 1976, the Supreme Court held that habeas corpus would not

be available at all for petitioners claiming that otherwise-reliable evidence

obtained in violation of the Fourth Amendment was used to convict them.

The next year, the Court would make it considerably harder

for petitioners who had failed to raise their objections in compliance with

state court rules to obtain relief in federal court on otherwise meritorious

claims.

Other judicial narrowings followed and then, in 1996,

Congress passed and President Bill Clinton signed the Antiterrorism and

Effective Death Penalty Act (AEDPA), which further limited habeas corpus.

The Court decisions and AEDPA have made it much more

difficult for prisoners without plausible constitutional claims that bear on

innocence to obtain relief via habeas corpus.

To my mind, that is understandable if not ideal:

understandable because innocents serving prison sentences or awaiting execution

suffer a much graver injustice than guilty parties whose proceedings were

tainted by constitutional error; not ideal because habeas review once served,

but no longer serves, as a means of ensuring that state court judges under

political pressure to be tough on crime give full effect to the constitutional

rights of criminal defendants.

But even if one thinks that Congress and the courts were

right to cut back on habeas in cases where prisoners raise claims that speak

only to the fairness of the proceedings, not to guilt or innocence, there is

cause for alarm.

Modern habeas law honors only half of Judge Friendly's

agenda. It makes the bringing of habeas petitions by guilty defendants

considerably harder than in the Warren Court era.

But it also makes it extremely difficult for the innocent to

obtain habeas relief. That proposition was on full display late last week in an

en banc ruling by the US Court of Appeals for the Seventh Circuit.

Spoiler Alert: I will now discuss a case that figures in the

Netflix documentary series Making a Murderer. If you intend to watch it but

have not yet done so, you might want to bookmark the column and come back here

after viewing.

For those readers who did not (and do not intend to) watch

or have forgotten the basic story of Making a Murderer, it goes like this:

(1) From 1985 to 2003, Steven Avery of Manitowoc County,

Wisconsin, served a prison sentence for a sexual assault he did not commit;

(2) after he was exonerated, Avery sued the county and

various police officials who were, the documentary indicates, at least grossly

negligent in the handling of his case;

(3) while the civil suit was pending, Avery was arrested for

the murder of photographer Teresa Halbach;

(4) the case against Avery was largely circumstantial,

including evidence that appeared to result from police tampering and other

improper procedure;

(5) that said, the police sometimes try to frame guilty

people, and I came away from Making a Murderer thinking that Avery might be

guilty of murdering Halbach, even if the evidence was thin;

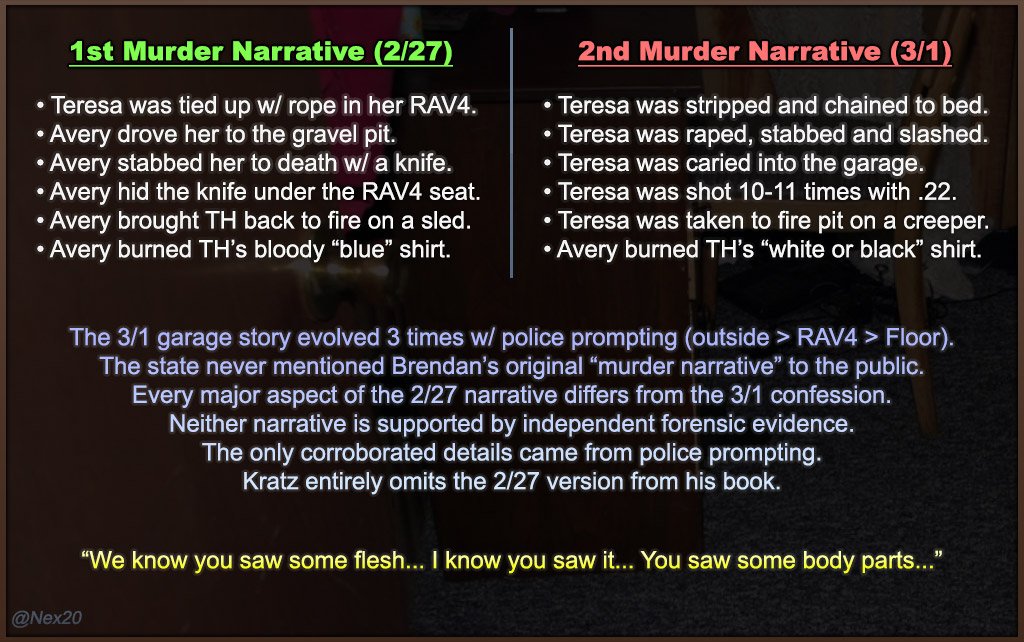

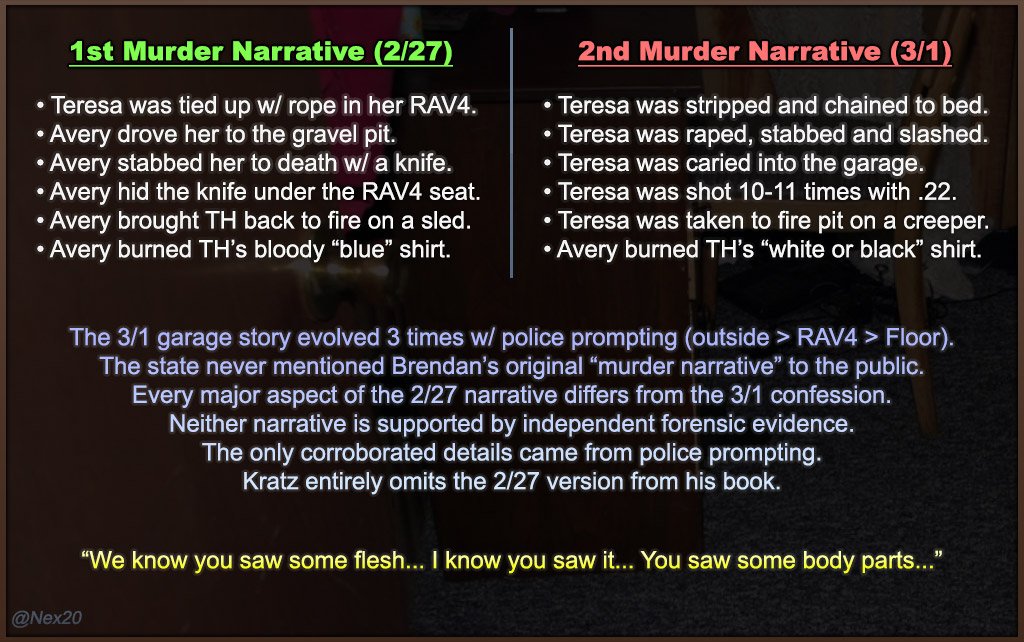

(6) the thinnest evidence was the confession of Avery's

nephew Brendan Dassey, who is close to intellectually disabled, who was

interviewed by police in an extremely suggestive manner, and who told a story

that was internally inconsistent and did not match the physical evidence on key

points;

(7) if the conviction of Avery appears dubious—I think the

jury ought to have found reasonable doubt, but at least he might be guilty—the

conviction of Dassey as an accomplice in the murder seems like a grave

injustice, because Dassey is very likely innocent.

Much of the Dassey-focused portion of Making a Murderer

illustrates how Dassey's first lawyer did a terrible job. The lawyer seems to

have concluded that Dassey was guilty without even meeting with him and without

ever considering the possibility that he might be innocent, gave damning

statements to the press, and hired a private investigator who was more or less

working for the police.

However, the key

evidence against Dassey was the video of an interview before his

ineffective lawyer began representing him.

On the basis of Dassey's recorded confession, the jury

convicted him of murder, and his state court appeals failed.

Despite the very high burden, Dassey obtained habeas relief from a federal district judge, who

concluded that the confession was involuntary. A panel of the Seventh Circuit affirmed, but last week the en banc

Seventh Circuit reversed by a vote of 4-3.

There is a difference between a documentary film and a full

trial record, so I read the majority opinion with an open mind, expecting to

learn that Making a Murderer had perhaps left out key details of the case

against Dassey.

To my surprise, I found none. Indeed, to the contrary, Judge

Hamilton's opinion for the court dutifully recites the inconsistencies in

Dassey's story, his seeming not to realize the nature of the interrogation

(indicating he was eager most of all to get back to class even after he had confessed

to a murder), the language used by the officers to indicate that if only Dassey

told them what they wanted to hear he would be free, and . . . nothing else.

Although the written account in the en banc opinion lacks

the full drama of Making a Murderer, like the documentary, the opinion paints a

picture of the events that strongly suggests that Dassey is innocent.

So why does the majority allow to stand a conviction based

on a confession that is at best of questionable reliability when there is no

other real evidence tying Dassey to the crime?

Because Dassey's likely innocence is, in a word, irrelevant.

Unlike the Fourth Amendment, which protects values like

privacy and property, which are not linked to a defendant's guilt or innocence

of the crime for which he is accused, the Fifth Amendment right against a

coerced confession is linked to guilt or innocence.

That's one reason why, in a 1993 case, the Supreme Court

refused to extend the no-Fourth-Amendment-exclusionary-rule-claims-on-habeas

rule to habeas petitions based on a claimed Miranda violation.

The Miranda warnings serve to mitigate the inherent

coerciveness of custodial interrogation with the aim of preventing coerced

confessions, and coerced confessions are unreliable evidence.

Strong evidence of guilt might be obtained in violation of

the Fourth Amendment, but evidence obtained via a coerced confession is not

strong evidence of guilt because the coercion, rather than the suspect's

conscience, will have been the basis for the confession.

Yet even though petitioners can bring Fifth Amendment claims

on habeas, the restrictive rules that were adopted by the Court beginning in

the early 1970s and then tightened further by Congress in AEDPA make it

difficult to prevail on Fifth Amendment claims, just as they make it difficult

to prevail on more "technical" claims that do not correlate with

guilt or innocence.

The Court and Congress heeded Judge Friendly's call to make

habeas relief much more difficult for guilty prisoners to obtain, but in so

doing they threw the baby out with the bathwater by also making habeas relief

much more difficult for innocent prisoners to obtain.

Thus, Judge Hamilton's en banc opinion notes that AEDPA sets

a high standard for relief and that Dassey hasn't met that standard. End of

story.

Is that right? Not necessarily. Here's how Judge Wood begins

her dissent:

Psychological coercion, questions to which the police

furnished the answers, and ghoulish games of ”20 Questions,” in which Brendan

Dassey guessed over and over again before he landed on the “correct” story

(i.e., the one the police wanted), led to the “confession” that furnished the

only serious evidence supporting his murder conviction in the Wisconsin courts.

Turning a blind eye to these glaring faults, the en banc

majority has decided to deny Dassey’s petition for a writ of habeas corpus.

They justify this travesty of justice as something compelled by AEDPA.

If the writ, as limited by AEDPA, were nothing more than a

dead letter, perhaps they would be correct. But it is not. Instead, as the

Supreme Court wrote in Harrington v. Richter, “the writ of habeas corpus

stands as a safeguard against imprisonment of those held in violation of the

law.”

It is, the Court went on to say, “a guard against extreme

malfunctions in the state criminal justice systems.”

As the district court and the panel majority recognized, we

have before us just such an extreme malfunction. Dassey at the relevant time

was 16 years old and had an IQ in the low 80s. His confession was coerced, and

thus it should not have been admitted into evidence.

And even if we were to overlook the coercion, the confession

is so riddled with input from the police that its use violates due process.

Dassey will spend the rest of his life in prison because of

the injustice this court has decided to leave unredressed. I respectfully

dissent.

Kudos to Judge Wood for trying to make lemonade from a

lemon, in particular Harrington v. Richter , in which the rhetoric she quotes

begins an opinion that goes on to deny relief to the habeas petitioner.

Kudos as well for strongly suggesting--even without exactly

saying--that Dassey should be granted relief because he is probably innocent.

Judge Wood only just barely failed.

The case was 4-3, after all. But Dassey would have had a

better chance of obtaining habeas relief if the full Friendly program had been

implemented and innocence were made an explicit basis for placing a thumb, or

better yet, an entire arm, on the scale in favor of relief.

Is this the end of the habeas road for Dassey?

Technically not. He could file a cert petition with the

Supreme Court, but his prospects there are doubtful. Ex ante, one would have

predicted a better chance of success before the Seventh Circuit.

Moreover, Dassey's case is mostly about the application of

law to facts and evidence, and thus not obviously cert-worthy on any issue of

larger importance.

Sure, it presents the larger question whether, as Friendly

asked, innocence is irrelevant, but the Supreme Court doesn't seem much

interested in that question.

There remains the desperate possibility that Dassey could

obtain federal habeas relief by filing an "actual innocence" claim.

The Supreme Court suggested the possibility of such a claim in Herrera v.

Collins in 1993, but it is not clear that actual innocence is a basis for

relief from a sentence of life imprisonment rather than only from a death

sentence.

And even if so, the Court has set an almost impossibly high

standard for relief based on actual innocence.

In the one case in which a habeas petitioner obtained any

relief from the SCOTUS on a Herrera claim, the Court said his lawyers needed to

go back to the district court and produce "evidence that could not have

been obtained at the time of trial [that] clearly establishes petitioner’s

innocence."

That petitioner, Troy Davis, was subsequently found not to

have produced such evidence and was executed.

Dassey could not, in any event, take advantage of the

Herrera/Davis opening, even if it were broader than a pinhole, because he is

not adducing new evidence.

Dassey's lawyers claim that the evidence that was adduced at

trial should not have been deemed adequate to convict him because his

confession was coerced and thus unreliable.

All that is left for Dassey, it seems, is the hope that

lightning strikes twice--that once again someone wholly unconnected to Steven

Avery is shown to have committed the crime for which Avery (and this time

Dassey as well) was convicted.

Michael C. Dorf is the Robert S. Stevens professor of law at

Cornell University. He blogs at DorfOnLaw.org.

By Tom Jackman, Washington Post

October 20, 2016

James L. Trainum, retired Washington, D.C., homicide

detective and author of the book “How the Police Generate False Confessions.

“If you plan on being arrested for a felony, you must read

this book.”— Tom Jackman, The Washington Post

Also, if you have an interest in fairness, justice and

preventing wrongful convictions, then the new book “How the Police Generate

False Confessions,” by former Washington, D.C., homicide detective James

Trainum is an important read. It takes you inside the interrogation room to see

how investigators extract admissions from innocent people, and how the justice

system can fix this persistent problem, seen in high profile cases such as the

Central Park Five, the Norfolk Four and the teenaged suspect from Wisconsin in

the Netflix series “Making a Murderer.”

It’s a phenomenon that remains, understandably,

incomprehensible to many. Someone “admits” to a crime they did not actually

commit, to a police detective of all people, knowing they face a long prison

sentence for doing so. Who would do such a thing? In all three of the cases

above, young men admitted to committing rape, and in two of them to gruesome

murders.

Trainum, 61, spent 17 years in homicide for the Metropolitan

Police Department, retiring in 2010. He was the lead detective on the

high-profile Starbucks triple murder in Georgetown in 1997, which he eventually

helped solve in 1999. But in 1994, Trainum had an eye-opening experience when he

obtained his own false confession. After a 16-hour interrogation, a woman told

him she and two men had killed a man whose body was found, bound and beaten,

near the Anacostia River. She was charged with first-degree murder. But she

recanted weeks later, and Trainum found proof that she couldn’t have been where

she originally claimed at the time of the slaying. The charges were dismissed.

“What did I do,” Trainum asked himself, “to convince this

person to tell me something she didn’t do? How did she get all those details

she shouldn’t have known?” He realized that implying that her cooperation would

get her better treatment from the prosecutors, and minimizing her role in the

case to obtain her testimony against co-defendants, as well as a mistaken

handwriting analysis and a bogus “voice stress test,” got her to confess.

Trainum began researching the concept of false confessions,

not widely discussed in the 1990s. At that time, five New York teenagers were

in prison for allegedly raping a woman in Central Park in 1989. Though DNA

later proved an unrelated man had committed the crime, some people still

believe the Central Park Five are guilty, including presidential candidate

Donald Trump. “It just shows you what the power of a confession is,” Trainum

said. “In spite of the overwhelming evidence, physical and otherwise, people

still believe a confession trumps everything. No pun intended.”

False confessions are now understood to be a significant

contribution to wrongful convictions. According to the National Registry of

Exonerations, of 1,900 wrongful convictions in their data base, 234 were caused

by false confessions, or about 12 percent.

Trainum said detectives are just following their training,

which is often minimal, and which allows for not only unethical tactics but

lying by investigators, who can falsely tell a suspect they failed a polygraph,

that other people identified him as a suspect and that evidence indicates he

committed the crime. Trainum summarizes the approach that most detectives take

to a suspect in “the box”:

1. Conclude that the suspect is guilty

2. Tell them that there is no doubt of their guilt

3. Block any attempt by the suspect to deny the accusation

4. Suggest psychological or moral justifications for what

they did

5. Lie about the strength of the evidence that points to the

suspect’s guilt

6. Offer only two explanations for why he committed the

crime. Both are admissions, but one is definitely less savory than the other

7. Get them to agree with you that they did it

8. Have them provide details about the crime

Now Trainum repeatedly acknowledges that police often elicit

confessions from actually guilty people, sometimes after long or difficult

sessions. But he said everyone in the system — detectives, defense attorneys,

prosecutors and judges — must be aware of the possibility of false confessions,

and be certain to do the legwork which corroborates or disproves such

statements.

In 1995, Washington, D.C., homicide detective Jim Trainum

was shown using the latest technology, and a new crime data base, to solve

cases. (Robert Reeder/The Washington Post)

Trainum writes that suspects often make false confessions

because they make a bad cost-benefit analysis. They think that confessing will

allow them to go home, or allow them to face lesser charges, or protect other

people. In “Making a Murderer,” 16-year-old Brendan Dassey confesses to murder

and then asks if he can return to class at his high school. That confession and

others were later used against him at trial and he was convicted, though in

August of this year the case was overturned after a federal judge ruled the

confessions were coerced and involuntary. “Thank God for videotape,” Trainum

said of the confession. “Those detectives were not seeking the truth. They’re

seeking a confession.”

But Dassey’s multiple confessions, including one in which

the detectives tell him how the victim was killed after he repeatedly provides

the wrong causes, had held up through trial and appeals court rulings for

years. “One of the biggest problems,” Trainum said, “is the judges don’t worry

about reliability [of a confession]. They say it’s up to the jury to decide

that. They only worry about if it is admissible. There’s kind of a movement to

shift the reliability back to the judges.” He noted that judges will hold

hearings on the reliability of eyewitnesses or the reliability of jailhouse

informants. “They don’t do that with confession evidence. And they really

should. Once a confession gets in front of a jury, the defense attorney has an

uphill battle. The jurors think, ‘I would never confess to something I didn’t

do.'”

The National Registry of Exonerations shows that 15 percent

of wrongful convictions occurred with guilty pleas. That was the case with

Danial Williams and Joseph Dick, two sailors in the Norfolk Four who falsely

confessed and pleaded guilty in the rape and murder of a woman in Norfolk in

1997. Another man’s DNA later linked him to the crime and he said he committed

it alone. Williams’ and Dick’s sentences were commuted but not fully pardoned by

then-Gov. Tim Kaine (now a vice presidential candidate) in 2009, and in an

appeal to have their convictions vacated, U.S. District Court Judge John A.

Gibney Jr. ruled last month that, “By any measure, the evidence shows the

defendants’ innocence…Stated more simply, no sane human being could find them

guilty.”

So what to do about false confessions? Trainum has many

suggestions, starting with police videotaping all interrogations. Many

departments still don’t do it. “Law enforcement doesn’t want you in that

interrogation room,” Trainum said. “They don’t want you to see what they’re

doing, because some of the stuff they know is not appropriate.”

But the ex-detective also advocates adopting the British

method of investigation, in which the questioning is not adversarial and is

instead focused on eliciting the truth, as opposed to only a confession. It is

known as P.E.A.C.E., for preparation, engagement, accounting, closure and evaluation.

It was imposed on British police after a spate of false confessions, and

Trainum said it can be used just as effectively as the current American method.

The P.E.A.C.E. model is only starting to make inroads in the

U.S., and it would require extensive training and money. He thinks the skill of

interviewing is undervalued. “People think talking to people is a natural

thing,” Trainum said. “It’s not. That’s why psychiatrists undergo so many years

of training. You have to be able to build a rapport without threats or

promises. Cops make the worst private investigators. We have too many bad

habits.”

Trainum, now a consultant for the Innocence Project, the

National Center for Missing and Exploited Children and various defense lawyers,

has not exactly been embraced by his former colleagues, who began calling him

“Benedict Trainum” when he was still on the force. He said he is shunned by some

older cops, but younger ones are more open to his ideas.

“I hope law enforcement reads my book,” Trainum said. “With

my consulting business, I want to be put out of business. I would rather they

make good cases that I can’t touch.”

I asked Brandon Garrett, a University of Virginia law

professor who has focused on wrongful convictions, about Trainum’s book. “It is

such an important new book,” Garrett said. “For decades, we have seen false

confession after false confession lead to tragic wrongful convictions of the

innocent while serious criminals go undetected.

The courts have done little to respond to abuses in the interrogation

room; if anything they have eroded constitutional protections, such as the

right to remain silent. Trainum explains

that for police, there is another way.

Overly coercive interrogation techniques not only produce false

confessions but they are not good at uncovering good information. In the U.K. and in more agencies in the U.S.,

police have changed gears, turning from psychologically coercive techniques to

information gathering techniques.

Trainum and his book are at the forefront of a revolution in police

interrogations.”

Now that’s a lot better book review quote than mine.

UPDATE DECEMBER 8, 2017

On August 12, 2016, Brendan Dassey's

2007 conviction was overturned by federal judge William E. Duffin. The State of Wisconsin appealed the decision. In June 2017, a three-judge panel for the U.S. Court of Appeals agreed 2-to-1 with Duffin's 2016 ruling. The State of Wisconsin appealed the decision. On December 8, 2017, the full seven-judge panel of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Seventh Circuit ruled by a vote of 4-to-3 that Brendan's confession had not been coerced by police investigators,

reversing the panel's decision.

“The state courts’ finding that Dassey’s confession was voluntary was not beyond fair debate, but we conclude it was reasonable. We reverse the grant of Dassey’s petition for a writ of habeas corpus,” Judge Hamilton wrote for the majority.

Hamilton said that Dassey was not subjected to threats or intimidation and investigators stayed calming while interviewing him.

Wood slammed the majority’s decision as “a profound miscarriage of justice.”

“Psychological coercion, questions to which the police furnished the answers, and ghoulish games of ‘20 Questions,’ in which Brendan Dassey guessed over and over again before he landed on the ‘correct’ story (i.e., the one the police wanted), led to the ‘confession’ that furnished the only serious evidence supporting his murder conviction in the Wisconsin courts,” Wood wrote. (Parentheses in original.)

The Seventh Circuit’s chief judge said Dassey’s confession was clearly coerced and should not have been admitted into evidence.

“Dassey will spend the rest of his life in prison because of the injustice this court has decided to leave unredressed,” Wood wrote. [Source]

END UPDATE

WBAY

June 23, 2017

Attorneys for "Making A Murderer" subject Brendan Dassey have filed a

motion asking for their client's immediate release from prison.

The motion was filed Friday with the United States Court of

Appeals for the Seventh Circuit, one day after a three-judge panel

upheld a lower court's ruling overturning Dassey's conviction for the

2005 murder of Teresa Halbach in Manitowoc County.

In the motion, attorneys Laura Nirider and Steve

Drizin ask the court to lift a stay that's blocking Dassey's release

from prison.

"Mr. Dassey, now twenty-seven years old, has

been held in custody since March 31, 2006 - since he was sixteen years

old - for a conviction, based almost entirely on an involuntary

confession, that has been overturned," reads the motion.

Judge William Duffin, who initially overturned

Dassey's conviction and ordered his release from prison, issued the

stay on request from the Wisconsin Department of Justice to allow the

agency time to appeal.

On Thursday, the appeals court released a 2-1

decision siding with Dassey that his confession to helping his uncle

Steven Avery rape and kill Halbach on Halloween 2005 was coerced by

Manitowoc County investigators.

Nirider and Drizin request that Dassey be released on bond.

"There is no longer any reason to further stay the district court's order releasing Mr. Dassey," reads the motion.

Click here to read the motion filed by Dassey's attorneys.

The order asks the state to file a response by

5 p.m. on June 26. Once it has heard from both sides, the court will

make a decision on Dassey's release. It could happen as early as next

week.

The Wisconsin Department of Justice has up to

three months to decide whether to re-try Dassey for Halbach's murder.

The state also has the option of asking the full 7th Circuit Court to

review the case, or taking it to the U.S. Supreme Court.

"We anticipate seeking review by the entire

7th Circuit or the United States Supreme Court and hope that today’s

erroneous decision will be reversed. We continue to send our condolences

to the Halbach family as they have to suffer through another attempt by

Mr. Dassey to re-litigate his guilty verdict and sentence," reads a

statement provided by the DOJ.

Two federal courts have now ruled that Dassey's

confession to Halbach's murder was involuntary, differing from decisions

in the state courts.

The federal appeals court's majority opinion

states that Dassey's intellectual limitations and suggestibility must be

taken into account, and the investigators gave him false promises of

leniency.

"Dassey's interview could be viewed in a

psychology class as a perfect example of operant conditioning," reads

the majority opinion.

"In sum, the investigators promised Dassey

freedom and alliance if he told the truth and all signs suggest that

Dassey took that promise literally. The pattern of questions

demonstrates that the message the investigators conveyed is that the

'truth' was what they wanted to hear."

Click here to view the 128-page opinion from the federal court of appeals.

Steven Avery's attorney visited her client

Friday at Waupun Correctional Institution. Kathleen Zellner tells Action

2 News that Avery is optimistic about his own case.

"He's extremely optimistic because

when someone's innocent, and I've done this many times, they always are

optimistic. I think he feels we have the evidence now to vacate the

conviction. which we will do, and so he's very optimistic," Zellner

said.

Zellner has filed a

post-conviction motion

arguing Avery should be granted a new trial based on five arguments,

including ineffective defense counsel, ethical violations by the

prosecutor, and new evidence. Zellner's motion breaks down new

scientific testing she had completed on evidence on the theory Avery's

DNA was planted.

Click here to view our exclusive interview with Kathleen Zellner.

Error in article above as noted by MnAtty at reddit:

WBAY wrote that (back in November) “Judge William Duffin, who initially overturned Dassey's conviction and ordered his release from prison, issued the stay on request from the Wisconsin Department of Justice to allow the agency time to appeal. WRONG. Judge Duffin DENIED this motion, stating it “largely

reargues the same points already considered and rejected by the court

in deciding Dassey's motion for release.” The WDOJ then filed an emergency motion with the Federal Appeals Court in Chicago, where their motion to stay was granted. WBAY really garbles these court rulings. Gotta watch out for that.

ORIGINAL POST FROM NOVEMBER 14, 2016

Federal Judge Orders Supervised Release of Brendan Dassey; Appeals Court Grants Stay of Release as Case Continues