June 1, 2012

http://wrongfulconvictionsblog.org/2012/05/10/cell-phone-evidence-doesnt-always-ring-true/

The post makes the point that data from a single cell tower is essentially worthless in trying to place someone in a particular location. The best you can expect is a band within a 120° “pie wedge” from the cell tower.

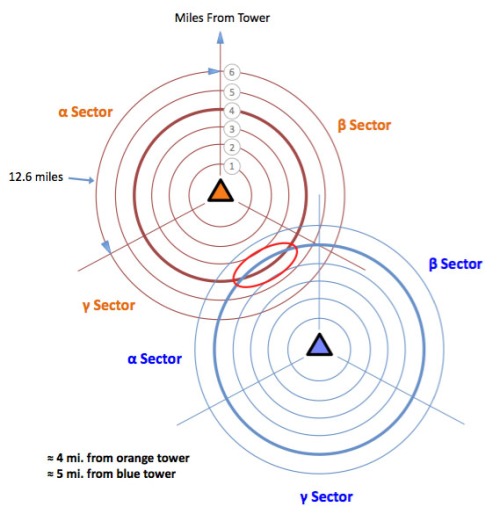

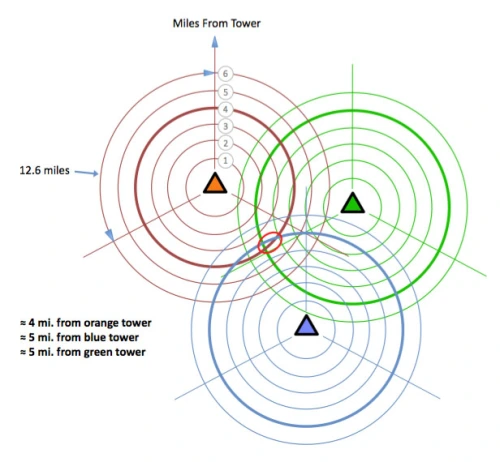

If two cell towers are used, it gets much better, and if three towers are used it gets even better yet. But to make sure this kind of evidence doesn’t get misused, and to know what it’s limitations are, it’s important to know how it works.

You may have noticed that the antennas on a cell tower are always arranged in a triangle. There are some sound technical and economic reasons for this, but we won’t go into that here. But it does mean that a cell tower can tell from which of the three antenna arrays it is receiving a signal. Each of the three antenna arrays covers a 120° sector with the tower at its focus, and these sectors, by convention, are referred to as alpha, beta, and gamma – α, β, γ.

Within each sector, the tower can make a measurement of how far away the transmitting cell phone is. This is done by measuring signal strength and the round-trip signal time. For a lot of technical reasons, this is not a very accurate measurement, and the determined distance will have a reasonably significant error band.

Here is a diagram of a single cell tower showing concentric bands of distance from the tower, and the three “sectors”. The distance bands don’t stop at “6”, but this is just to give you the idea. Note that at six miles out, the arc of a sector is 12.6 miles long.

Here is how a single-tower location would work. The cell tower has determined that the signal is coming from the γ sector, and that the origin of the signal is approximately 4 miles from the tower. This would place the caller within the yellow band, which you can see is 8.4 miles long and “about” ½ mile wide – an area of 4.2 square miles.

If the cell phone in question is also negotiating with a second cell tower at the same time (and this must be the case), the ability to locate the phone gets much better.

Here is a diagram of the situation when the phone is 4 miles from the “orange” tower in the γ sector, and 5 miles from the “blue” tower in the α sector. This will place the phone in an oval (shown in red) whose center is the intersection of the swept areas of the two towers’ approximate distance bands.

If a third tower is brought into play, and the phone in question is determined to be 5 miles from the (third) “green” tower, this diagram shows that the area of location can be estimated even more closely. Keep in mind that the phone must be negotiating with all three towers at the same time.

In densely populated urban areas, the cell towers are close together, and a much closer estimation of phone location can be made than in a rural area, where the towers are far apart.

Some of the newest cell phones can actually report a GPS location, and this is quite accurate, and doesn’t rely on the cell towers at all.

Using cell tower triangulation (3 towers), it is possible to determine a phone location to within an area of “about” ¾ square mile.

Cell tower locating evidence often goes unchallenged by the defense. Now that you have the basics, you should be in a position to challenge that kind of evidence when it’s called for.

Generally speaking, if you have good line of sight, then the sectors point north, southeast, and southwest.

However, if you don't have good line of sight in those directions, they will turn them to the best positions possible to cover as much area as possible.

Therefore, in reality, it can vary very much, so the directional sectors listed below are approximated:

1 — approximately N to NE;

2 — 120° clockwise from 1 --- approximately SE to S;

3 — 120° clockwise from 2 --- approximately W.

By Larry E. Daniel

Spring 2014

It is impossible to determine the distance the phone is from a cell tower at any particular time, and suggesting that the phone is within an arbitrary boundary drawn on a map is inherently false. While some analysts will attempt to use per call measurement (PCM) data to show the distance of the phone from the tower at the time the call was made, PCM data can be off as much as four miles when actually measured against the tower locations and the PCM global positioning (GPS) coordinates provided for that particular phone call.

Cell sectors do not conform to a pie shape, nor is the coverage area a circle.

If you study the propagation maps at this link (pages 13-16) with the cell sectors drawn, it is easy to see that the circles and pie shapes have little to no relationship to the way that radio waves actually work.

In fact, if you look at the yellow area in the map below, you can see not only an irregular shape for the cell sector, a large portion of the cell sector’s coverage is disconnected from the tower, creating hot spots where a phone can make a call without being anywhere near the tower.

The map below illustrates the wide variation in radio coverage at ground level for cell tower sectors in an area.

The map shows that the radio coverage of cell towers and sectors is not limited to a precise circle or pie shape and, in fact, that the radio coverage varies a great deal from tower to tower and sector to sector and from day to day.

Note that the drive test area of coverage outlined in black in the figure below has a vastly different shape than the pie slice shown in yellow for the coverage area. The yellow pin represents a location where the suspect was supposed to have been, but the map shows that the phone could have been in the coverage area of a different cell tower at the time of the call.

Cell phone tracking from call detail records and tower locations would not meet the criteria to be a forensically sound method; nor would drive testing or propagation modeling, as both of these methods would produce a different result over a period of time.

Properly applied and interpreted cell phone location evidence can be helpful in many cases. The issue is the overstatement of the accuracy of the phone’s location. For instance, if the phone is using a cell tower in a particular town where an incident occurred and the person who was in possession of the phone claims to have been in a different town, it is a simple presentation to dispute the person’s claim.

Another good use is for tracking a phone across a distance based on cell tower usage. While the analyst cannot claim a particular road was used, the cellular evidence can certainly illustrate for a jury that the phone did in fact travel from one city to another or some area to another.

In a recent case cell tower evidence was used to show that a phone call was made near the location of the defendant’s home and a subsequent call was located near his place of employment. At issue was whether or not it would be possible for the defendant to travel to another location, commit a burglary and still make it to the location near his work in the time span between the calls. By combining the cell phone locations, time estimates from Google Maps and the location of the burglary, the jury was convinced that the defendant could not have committed the burglary and still made it to the location of his work in rush hour traffic in Washington, DC.

Cellular evidence can also be used to show that a phone was near a particular area of interest with some reasonable confidence. And the more data points used can be helpful in showing that even if the analyst cannot determine why the phone picked a particular tower, dozens of uses of the same tower in a short time would lend itself to showing that the phone was using that tower over other towers nearby on a consistent basis.

Cell phones attempt to connect with the tower emitting the strongest and highest quality signal at a given moment, not the closest.

The actual determination of which cell tower is used is complex and hinges on a multitude of factors that are not memorialized in the call detail records. There is no data provided to determine why that particular tower was used for the call, only that a particular tower was recorded in the call detail records as having been used at the time for the call.

Many factors come into play in the selection of a tower to handle a cellular phone call, and these factors are specific to the moment in time when the call is connected. Such factors include:

The physical location of the cell tower masts is factual in basis because cellular carriers maintain the geo-location (GPS) coordinates of cell towers and provide those GPS locations to the expert for use in his plotting of the locations of the towers.

However, there are no published set of principles or methods governing the estimation of cell tower coverage based on simply drawing circles on a map where the circles overlap based on the distance from one tower to other adjacent towers, the size of the circles being determined by the distance between cell towers.

In fact, the distance between cell towers on a map have no real bearing on the coverage area of the cell tower at all for the following reasons:

The inherent issue with using maps with circles and pie shapes drawn in to illustrate the approximate location of a cell phone is that it gives the incorrect impression, bolstered by expert testimony, that the cell phone location is limited to the area defined by the circle or pie shape.

Since it is impossible to determine the distance the phone is from a cell tower at any particular time, suggesting that the phone is within an arbitrary boundary drawn on a map is inherently false.

While some analysts will attempt to use per call measurement (PCM) data to show the distance of the phone from the tower at the time the call was made, in my experience, PCM data can be off as much as four miles when actually measured against the tower locations and the PCM global positioning (GPS) coordinates provided for that particular phone call.

The image below demonstrates the difference between an idealized layout of a cell network, and the theoretical service areas of three sectors within the network.

As shown in the figure above, cell sectors do not conform to a pie shape, nor is the coverage area a

circle.

A single cell site (usually a mast or building) can contain the hardware for several cells, which are then also known as sectors. Typically, there will be three sectors per cell site and each sector will usually point in a different direction (known as the azimuth) but this can vary, usually between one and six.

The sectors will operate independently of each other, having unique Cell IDs usually related to each other and similar to the code for the covering cell site.

Each sector will provide service over a particular geographical area, and this area will not be uniform (i.e. it will not be a circle, a triangle or any other regular shape); there may be many different shapes according to geography and the need of the network (e.g. long thin cells on motorways).

There may also be disconnected areas of service known as hotspots.

The two primary methods for “sharing” radio channels are Time Division Multiple Access (TDMA), which is used in the Global System for Mobile Communications (GSM) network and Code Division Multiple Access (CDMA) which is used in the CDMA network.

AT&T (which merged with Cingular starting in 2004) is a GSM wireless company and Sprint is a CDMA wireless company.

There are three issues that drive cell tower range:

If the signal can't go through, it might make it around by reflection and diffraction, but these are very local and hard to predict. This is why you might find a cell phone will work when you stand in one spot, but if you move three meters, it stops working.

Absolute maximum range for standard GSM is 35 km. This is dictated by the Timing Advance range being restricted to values between zero and 63, with each step corresponding to 553.5 meters from the tower.

By L. Scott Harrell

Published 2008

A cell phone “ping” is quite simply the process of determining the location, with reasonable accuracy, of a cell phone at any given point in time by utilizing the phone GPS location aware capabilities (it is very similar to GPS vehicle tracking systems).

To “ping” in this context means to send a signal to a particular cell phone and have it respond with the requested data.

Similar technology is used to track down lost aircraft and yachts through their radio beacons. It’s not identical because most radio beacons use satellites and older cell phones use land-based aerial arrays, but the principle is the same.

Some nefarious service providers have indicated that they have either developed sources within mobile telephone service providers to be able to get this information upon request or have access to the software interfaces to accomplish this on their own (or some variant thereof). I highly suspect that these “cell phone ping service providers” I see advertising from time to time are actually using a good ol’ fashioned pretext to obtain the location of a cell phone rather than using an actual ping. If you do come across a real provider, please let me know.

Spring 2014

It is impossible to determine the distance the phone is from a cell tower at any particular time, and suggesting that the phone is within an arbitrary boundary drawn on a map is inherently false. While some analysts will attempt to use per call measurement (PCM) data to show the distance of the phone from the tower at the time the call was made, PCM data can be off as much as four miles when actually measured against the tower locations and the PCM global positioning (GPS) coordinates provided for that particular phone call.

Cell sectors do not conform to a pie shape, nor is the coverage area a circle.

If you study the propagation maps at this link (pages 13-16) with the cell sectors drawn, it is easy to see that the circles and pie shapes have little to no relationship to the way that radio waves actually work.

In fact, if you look at the yellow area in the map below, you can see not only an irregular shape for the cell sector, a large portion of the cell sector’s coverage is disconnected from the tower, creating hot spots where a phone can make a call without being anywhere near the tower.

The map below illustrates the wide variation in radio coverage at ground level for cell tower sectors in an area.

The map shows that the radio coverage of cell towers and sectors is not limited to a precise circle or pie shape and, in fact, that the radio coverage varies a great deal from tower to tower and sector to sector and from day to day.

Note that the drive test area of coverage outlined in black in the figure below has a vastly different shape than the pie slice shown in yellow for the coverage area. The yellow pin represents a location where the suspect was supposed to have been, but the map shows that the phone could have been in the coverage area of a different cell tower at the time of the call.

Cell phone tracking from call detail records and tower locations would not meet the criteria to be a forensically sound method; nor would drive testing or propagation modeling, as both of these methods would produce a different result over a period of time.

Properly applied and interpreted cell phone location evidence can be helpful in many cases. The issue is the overstatement of the accuracy of the phone’s location. For instance, if the phone is using a cell tower in a particular town where an incident occurred and the person who was in possession of the phone claims to have been in a different town, it is a simple presentation to dispute the person’s claim.

Another good use is for tracking a phone across a distance based on cell tower usage. While the analyst cannot claim a particular road was used, the cellular evidence can certainly illustrate for a jury that the phone did in fact travel from one city to another or some area to another.

In a recent case cell tower evidence was used to show that a phone call was made near the location of the defendant’s home and a subsequent call was located near his place of employment. At issue was whether or not it would be possible for the defendant to travel to another location, commit a burglary and still make it to the location near his work in the time span between the calls. By combining the cell phone locations, time estimates from Google Maps and the location of the burglary, the jury was convinced that the defendant could not have committed the burglary and still made it to the location of his work in rush hour traffic in Washington, DC.

Cellular evidence can also be used to show that a phone was near a particular area of interest with some reasonable confidence. And the more data points used can be helpful in showing that even if the analyst cannot determine why the phone picked a particular tower, dozens of uses of the same tower in a short time would lend itself to showing that the phone was using that tower over other towers nearby on a consistent basis.

Cell phones attempt to connect with the tower emitting the strongest and highest quality signal at a given moment, not the closest.

The actual determination of which cell tower is used is complex and hinges on a multitude of factors that are not memorialized in the call detail records. There is no data provided to determine why that particular tower was used for the call, only that a particular tower was recorded in the call detail records as having been used at the time for the call.

Many factors come into play in the selection of a tower to handle a cellular phone call, and these factors are specific to the moment in time when the call is connected. Such factors include:

a. the loading of the towers in the area, which means, which tower has the available capacity at that moment in time to handle the call.There is no factual basis for drawing coverage circles or pie shapes on a map, and the cellular company does not provide such data to experts in cases.

b. the health of the towers in the area at the moment in time, which means, are all towers fully functioning at the time of the call.

c. line of sight to the tower from the cellular phone itself.

d. radio signal interference from other cell towers in the area.

e. the make and model and condition of the particular cell phone being used.

f. multi-pathing, which is a function of the terrain as well as both natural and man-made clutter in the area such as trees, hills, buildings and signs that cause radios waves to be either reflected or absorbed, also referred to as Rayleigh fading.

g. the strength and quality of signal from the towers around the cell phone.

h. whether the phone is inside a building or outside at the time the call was recorded, where structural materials may block the signal from one tower, forcing the cell phone to select a different tower than one it would be able to connect with if it were outdoors.

The physical location of the cell tower masts is factual in basis because cellular carriers maintain the geo-location (GPS) coordinates of cell towers and provide those GPS locations to the expert for use in his plotting of the locations of the towers.

However, there are no published set of principles or methods governing the estimation of cell tower coverage based on simply drawing circles on a map where the circles overlap based on the distance from one tower to other adjacent towers, the size of the circles being determined by the distance between cell towers.

In fact, the distance between cell towers on a map have no real bearing on the coverage area of the cell tower at all for the following reasons:

a. Cell towers are placed based on anticipated load, which is the maximum number of cell phone calls anticipated at peak load times for the cell tower. Thus the expected coverage area can vary widely between cell towers.Cell tower coverage does not fit into neatly drawn circles or pie shapes.

b. Cell towers are not always configured to provide the same amount of antenna power output, which determines the maximum range of the signal produced by the antennas.

c. Cell towers are placed to cover specific areas by either mechanically or electronically tilting the antennas toward the ground and are not configured to cover an area shown as a perfect circle on a map.

d. Not all tower antennas have the same beamwidth. Beamwidth is the width of the antenna signal defined in degrees. The most widely used analogy to describe beamwidth is to think of the antenna as projecting a beam of light, in the same way that a flashlight beam projects. As the beam exits the flashlight it spreads out in a pattern. In the same say that some flashlights can adjust the width of the beam of light to become wider or narrower, the antennas on a cell tower canbe adjusted to project a wider or narrower beam of radio signals. In the absence of the beamwidth being provided by the carrier for each sector, it is common to “assume” a beamwidth of 120 degrees. This is an assumption and should not be allowed to be used as evidence when such data is not provided by the cellular company.

e. Each cell tower that contains sector antennas can have two or more of these antennas pointing in different compass directions. Each of the antennas can be configured independent of the other antennas to suit the coverage need for that particular tower. In other words, the antennas can each have a different down tilt, beamwidth and a specified direction for the antenna. While the azimuth, which is the direction the antenna points, maybe provided in the tower locations records, the actual coverage area of the sector antenna can vary widely even between sector antennas on the same tower mast.

f. In today’s cellular system environment, many cell towers contain more than a single set of antennas for a carrier, making it even more difficult to use the standard three sector antenna idea to estimate the coverage area.

The inherent issue with using maps with circles and pie shapes drawn in to illustrate the approximate location of a cell phone is that it gives the incorrect impression, bolstered by expert testimony, that the cell phone location is limited to the area defined by the circle or pie shape.

Since it is impossible to determine the distance the phone is from a cell tower at any particular time, suggesting that the phone is within an arbitrary boundary drawn on a map is inherently false.

While some analysts will attempt to use per call measurement (PCM) data to show the distance of the phone from the tower at the time the call was made, in my experience, PCM data can be off as much as four miles when actually measured against the tower locations and the PCM global positioning (GPS) coordinates provided for that particular phone call.

The image below demonstrates the difference between an idealized layout of a cell network, and the theoretical service areas of three sectors within the network.

As shown in the figure above, cell sectors do not conform to a pie shape, nor is the coverage area a

circle.

A single cell site (usually a mast or building) can contain the hardware for several cells, which are then also known as sectors. Typically, there will be three sectors per cell site and each sector will usually point in a different direction (known as the azimuth) but this can vary, usually between one and six.

The sectors will operate independently of each other, having unique Cell IDs usually related to each other and similar to the code for the covering cell site.

Each sector will provide service over a particular geographical area, and this area will not be uniform (i.e. it will not be a circle, a triangle or any other regular shape); there may be many different shapes according to geography and the need of the network (e.g. long thin cells on motorways).

There may also be disconnected areas of service known as hotspots.

The two primary methods for “sharing” radio channels are Time Division Multiple Access (TDMA), which is used in the Global System for Mobile Communications (GSM) network and Code Division Multiple Access (CDMA) which is used in the CDMA network.

AT&T (which merged with Cingular starting in 2004) is a GSM wireless company and Sprint is a CDMA wireless company.

There are three issues that drive cell tower range:

1). Height. Cell phone is line of sight. In urban areas, you tend to run out of transmit power before you run out of line of sight range.If you are on the roof of a two-story houses, the range can be quite long. Get down on the ground and the range becomes much shorter. The problem is that the signal must travel by line of sight (more or less). If you can see the tower antenna, you'll probably have a full strength signal. Otherwise, the signal must travel along the slant range through (or around) all the intervening junk. What exactly is the attenuation of a UHF signal passing through brick, stone, aluminum siding, wood, reinforced concrete? This "junk" kills radio signals. The water in trees does a pretty good job on signals too.

2). Power output. GSM defines several power output classes, depending upon the requirements. There is a minimum signal strength required to maintain an acceptable call. These are typically in the 5-20 watt class, although up to 200 watts is defined. You may find a 200 watt on top a big hill in a rural area.... The 5-20 watts effectively limits the range to something in the 5-8 mile range, somewhat more in open country.

3). Timing advance. GSM operates within narrow timing constraints, so that the signal arrival at the BTS has to fall within the window. To achieve this, the timing at the handset is 'tweaked' under BTS control. The limit on timing advance is 35 km (21.7479917 miles). If you want to get past 35 km, something has to give. It has been done in Rural Australia, but it means giving up 4 of the 8 time slots so that the signal from the handset no longer has to arrive within its own slot. The next time slot is sacrificed.

If the signal can't go through, it might make it around by reflection and diffraction, but these are very local and hard to predict. This is why you might find a cell phone will work when you stand in one spot, but if you move three meters, it stops working.

Absolute maximum range for standard GSM is 35 km. This is dictated by the Timing Advance range being restricted to values between zero and 63, with each step corresponding to 553.5 meters from the tower.

By L. Scott Harrell

Published 2008

I hesitated to include this article

since cell phone pinging has always been something of an urban legend

among the private investigation and bail enforcement communities.

However, I do know for certain that it is absolutely possible and that

many fugitives and abducted children have been recovered through the use

of cell phone pinging by various State and Federal law enforcement

agencies.

Do you remember when President Bush went

to the Middle East on a surprise visit to the troops not too long ago?

The media made a big deal about the  fact that the Secret Service made

everyone onboard Air Force One, including the President, take the

battery out of their cell phones so that the “real bad guys” didn’t know

of their location.

fact that the Secret Service made

everyone onboard Air Force One, including the President, take the

battery out of their cell phones so that the “real bad guys” didn’t know

of their location.

fact that the Secret Service made

everyone onboard Air Force One, including the President, take the

battery out of their cell phones so that the “real bad guys” didn’t know

of their location.

fact that the Secret Service made

everyone onboard Air Force One, including the President, take the

battery out of their cell phones so that the “real bad guys” didn’t know

of their location.

Voila! (Cell phone pinging has gotten

someone’s attention.) I was convinced to include the article because a

trusted peer indicated that he too had luck with a locate at one time,

and anyone interested in locating another person may at least have the

need to understand the technology and the process of locating cellular

phones.

There are two ways a cellular network

provider can locate a phone connected to their network, either through

pinging or triangulation. Pinging is a digital process and triangulation

is an analog process.

A cell phone “ping” is quite simply the process of determining the location, with reasonable accuracy, of a cell phone at any given point in time by utilizing the phone GPS location aware capabilities (it is very similar to GPS vehicle tracking systems).

To “ping” in this context means to send a signal to a particular cell phone and have it respond with the requested data.

The term is derived from SONAR and

echolocation when a technician would send out a sound wave, or ping, and

wait for its return to locate another object.

New generation cell phones and mobile service providers are required by federal mandate, via the “E-911” program, to be or become GPS capable so that 911 operators will be able to determine the location of a caller who is making an emergency phone call.

When a new digital cell phone is pinged, it determines its latitude and longitude via GPS and sends these coordinates back via the SMS system (the same system used to send text messages).

This means that in instances where a fugitive or other missing person has a GPS-enabled cell phone (and that the phone has power when being polled or pinged) that the cell phone can be located within a reasonable geographic area — some say within several feet of the cell phone.

New generation cell phones and mobile service providers are required by federal mandate, via the “E-911” program, to be or become GPS capable so that 911 operators will be able to determine the location of a caller who is making an emergency phone call.

When a new digital cell phone is pinged, it determines its latitude and longitude via GPS and sends these coordinates back via the SMS system (the same system used to send text messages).

This means that in instances where a fugitive or other missing person has a GPS-enabled cell phone (and that the phone has power when being polled or pinged) that the cell phone can be located within a reasonable geographic area — some say within several feet of the cell phone.

With the older style analog cellular

phones and digital mobile phones that are not GPS capable, the cellular

network provider can determine where the phone is to within a hundred

feet or so using “triangulation” because at any one time, the phone is

usually able to communicate with more than one of the aerial arrays

(antennas) provided by the phone network.

The cell towers are typically 6 to 12 miles apart (less in cities) and a phone is usually within range of at least three of them. By comparing the signal strength and time lag for the phone’s carrier signal to reach at each tower, the network provider can triangulate the phone’s approximate position.

The cell towers are typically 6 to 12 miles apart (less in cities) and a phone is usually within range of at least three of them. By comparing the signal strength and time lag for the phone’s carrier signal to reach at each tower, the network provider can triangulate the phone’s approximate position.

Similar technology is used to track down lost aircraft and yachts through their radio beacons. It’s not identical because most radio beacons use satellites and older cell phones use land-based aerial arrays, but the principle is the same.

Not surprisingly, the phone network

companies are shy about admitting they have this ability.

The triangulation and pinging capability of mobile phone network companies varies according to the age of their equipment. A few can only do it manually with a big drain on skilled manpower. But these days most companies can generate the information automatically, which makes it cheap enough to sell.

The triangulation and pinging capability of mobile phone network companies varies according to the age of their equipment. A few can only do it manually with a big drain on skilled manpower. But these days most companies can generate the information automatically, which makes it cheap enough to sell.

Some nefarious service providers have indicated that they have either developed sources within mobile telephone service providers to be able to get this information upon request or have access to the software interfaces to accomplish this on their own (or some variant thereof). I highly suspect that these “cell phone ping service providers” I see advertising from time to time are actually using a good ol’ fashioned pretext to obtain the location of a cell phone rather than using an actual ping. If you do come across a real provider, please let me know.

There you have it — the short course

regarding the technical capability of locating cell phones and those who

possess them either through pinging or triangulation. Again, I cannot

speak to the commercial availability of such a service but like anything

else in the investigative business; for now I believe that mobile-phone

pinging is largely urban myth among private investigators, fugitive

recovery investigators and skip tracers.

What Your Cell Phone Can’t Tell the Police

By Douglas Starr, The New Yorker

June 26, 2014

On May 28th, Lisa Marie Roberts, of Portland, Oregon, was released from prison after serving nine and a half years for a murder she didn’t commit. A key piece of overturned evidence was cell phone records that allegedly put her at the scene.

Roberts pleaded guilty to manslaughter in 2004 after her court-appointed attorney persuaded her that she had no hope of acquittal. The state’s attorney had told him that phone records had put Roberts at the scene of the crime, and, to her lawyer, that was almost as damning as DNA. But he was wrong, as are many other attorneys, prosecutors, judges and juries who overestimate the precision of cell phone location records.

Rather than pinpoint a suspect’s whereabouts, cell tower records can put someone within an area of several hundred square miles or, in a congested urban area, several square miles. Yet years of prosecutions and plea bargains have been based on a misunderstanding of how cell networks operate. No one knows how often this occurs, but each year police make more than a million requests for cell phone records. “We think the whole paradigm is absolutely flawed at every level, and shouldn’t be used in the courtroom,” Michael Cherry, the C.E.O. of Cherry Biometrics, a consulting firm in Falls Church, Virginia, told me. “This whole thing is junk science, a farce.”

The paradigm is the assumption that, when you make a call on your cell phone, it automatically routes to the nearest cell tower, and that by capturing those records police can determine where you made a call—and thus where you were—at a particular time. That, he explained, is not how the system works.

When you hit “send” on your cell phone, a complicated series of events takes place that is governed by algorithms and proprietary software, not just by the location of the cell tower.

First, your cell phone sends out a radio-frequency signal to the towers within a radius of up to roughly twenty miles—or fewer, in urban areas—depending on the topography and atmospheric conditions. A regional switching center detects the signal and determines whether to accept the call. There are hundreds of such regional centers across the country.

The switching center determines the destination of your call and connects to the land lines that will take it to cell towers near the destination. Almost simultaneously, the software “decides” which of half a dozen towers in your area you’ll connect with. The selection is determined by load-management software that incorporates dozens of factors, including signal strength, atmospheric conditions, and maintenance schedules.

The system is so fluid that you could sit at your desk, make five successive cell calls and connect to five different towers. During a conversation, your signal could be switched from one tower to the next; you’ll also be “handed off” to another tower if you travel outside your coverage area while you’re speaking.

Designed for business and not tracking, call detail records provide the kind of information that helps cell companies manage their networks, not track phones.

If I make a cell call from Kenmore Square, in my home town of Boston, you might think that I’m connecting to a cell site a few hundred feet away. But, if I’m standing near Fenway Park during a Red Sox game, with thousands of fans making calls and sending texts, that tower may have reached its capacity. Hypothetically, the system might send me to the next site, which might also be at capacity or down for maintenance, or to the next site, or the next. The switching center may look for all sorts of factors, most of which are proprietary to the company’s software. The only thing that you can say with confidence is that I have connected to a cell site somewhere within a radius of roughly twenty miles.

Aaron Romano, a Connecticut lawyer who says that he has seen many cases involving cell records, has done a series of calculations to show how imprecise these locations can be. If you suppose that a cell tower has picked up a signal from ten miles away, you’re looking at a circle with a radius of ten miles, which has an area of three hundred and fourteen square miles. Cell tower coverage is divided into sectors. Most towers have three directional antennae, each of which covers one third of the circle. Including that factor gives you a sector of 104.67 square miles. “That’s a huge area,” Romano said. “So how can anyone say, with any degree of certainty, that a handset was at the scene of the crime?”

Some technologies can locate you precisely. If you carry an iPhone, you’re also carrying a G.P.S. transmitter, which links to a ground station and then to several satellites, which can find your location to within fifty to a hundred feet. You enable the G.P.S. when you use certain software, such as Google Maps. Similarly, if you make an emergency 911 call, your company will use three towers to triangulate your location; if you’re using a smartphone, it will use G.P.S. to pinpoint where you are.

If you’re the target of an ongoing investigation and law-enforcement agencies want to track you, they can ask a phone company to “ping” your phone in real time. (They also use that technique when trying to find a kidnapping victim.) Those methods are not what’s captured by phone-company cell tower records of the sort that helped put Roberts in prison.

When investigating a crime that occurred in the past, police tend to have two options: seize the G.P.S. chip and download the locations or obtain the cell records. Wednesday’s Supreme Court decision made it mandatory for police to obtain warrants before searching the cell phones of people they arrest. But the case law on getting cell tower information is split. In most jurisdictions, police can obtain your call detail records without a warrant. The disparity in requirements between the two could encourage police to rely increasingly on call detail records, Hanni Fakhoury, a staff attorney for the Electronic Frontier Foundation, said.

Put another way, if I’m making a cell phone call from my couch and someone commits a murder in a bar half a mile away, my cell records may serve as corroborating evidence that I took part in the crime. That might be true if I’d claimed to be in another state at the time, but those records cannot place me next to the body. What they don’t show is the precise location of a cell phone. Yet prosecutors often present those records as if they were DNA.

A few years ago, the F.B.I. established a unit specializing in cell records, called C.A.S.T. (Cellular Analysis and Surveillance Team), with the mission of analyzing cell location evidence. The Bureau declined requests for an interview, but C.A.S.T. agents in recent cases have asserted a different theory of how cell networks operate. Testifying at a trial for murder and robbery in Florida in June, 2013, Special Agent David Magnuson said that the instant a call is received or placed, it’s the phone that decides which tower to go to—not the software that adjusts network load—and that, “ninety-nine per cent of the time, it’s the closest tower.” Although he conceded that cell records can be imprecise, he described them as “like a historical digital fingerprint.” He added that the F.B.I. checks its information by doing periodic “drive tests,” in which it measures radio-frequency information emitted by cell towers to see if the coverage area agrees with its models.

Independent experts I spoke to called this testimony into question—both the accuracy of the estimates and the validity of the drive tests. Conditions are so changeable that, even if a drive test confirms the model on a particular day, it may not on another, and certainly not on a day years in the past. It’s a probabilistic statement, not a scientific one.

In 2012, the U.S. District Court for the Northern District of Illinois ruled that an F.B.I. agent could not testify about the location of a defendant’s cell phone because the analyses did not rise to the level of trusted, replicable science. Other courts have found for the defendant after the defense attorney discredited the prosecution’s expert witness.

Lisa Marie Roberts’s original lawyer wasn’t one of them. There were reasons to suspect her: she had a tumultuous, sometimes violent relationship with the victim, Jerri Williams. Cell records showed that at 10:27 on the morning of the murder, Roberts’s phone connected to a tower within 3.4 miles of Kelley Point Park, where Williams’s body was discovered. Her attorney felt that was enough to convict her.

But she was making that call while driving a red pickup truck more than eight miles away, as confirmed by a witness. The system had simply routed her call through the tower near the park. It also emerged that new DNA evidence placed another suspect, a man, at the crime scene. And another piece of evidence helped: moments earlier, Roberts had received another call that came through a different site. The two towers were 1.3 miles apart. She could not have traveled that distance in the forty seconds between the calls. And so her cell records, in a sense, helped to save her.

What Your Cell Phone Can’t Tell the Police

By Douglas Starr, The New Yorker

June 26, 2014

On May 28th, Lisa Marie Roberts, of Portland, Oregon, was released from prison after serving nine and a half years for a murder she didn’t commit. A key piece of overturned evidence was cell phone records that allegedly put her at the scene.

Roberts pleaded guilty to manslaughter in 2004 after her court-appointed attorney persuaded her that she had no hope of acquittal. The state’s attorney had told him that phone records had put Roberts at the scene of the crime, and, to her lawyer, that was almost as damning as DNA. But he was wrong, as are many other attorneys, prosecutors, judges and juries who overestimate the precision of cell phone location records.

Rather than pinpoint a suspect’s whereabouts, cell tower records can put someone within an area of several hundred square miles or, in a congested urban area, several square miles. Yet years of prosecutions and plea bargains have been based on a misunderstanding of how cell networks operate. No one knows how often this occurs, but each year police make more than a million requests for cell phone records. “We think the whole paradigm is absolutely flawed at every level, and shouldn’t be used in the courtroom,” Michael Cherry, the C.E.O. of Cherry Biometrics, a consulting firm in Falls Church, Virginia, told me. “This whole thing is junk science, a farce.”

The paradigm is the assumption that, when you make a call on your cell phone, it automatically routes to the nearest cell tower, and that by capturing those records police can determine where you made a call—and thus where you were—at a particular time. That, he explained, is not how the system works.

When you hit “send” on your cell phone, a complicated series of events takes place that is governed by algorithms and proprietary software, not just by the location of the cell tower.

First, your cell phone sends out a radio-frequency signal to the towers within a radius of up to roughly twenty miles—or fewer, in urban areas—depending on the topography and atmospheric conditions. A regional switching center detects the signal and determines whether to accept the call. There are hundreds of such regional centers across the country.

The switching center determines the destination of your call and connects to the land lines that will take it to cell towers near the destination. Almost simultaneously, the software “decides” which of half a dozen towers in your area you’ll connect with. The selection is determined by load-management software that incorporates dozens of factors, including signal strength, atmospheric conditions, and maintenance schedules.

The system is so fluid that you could sit at your desk, make five successive cell calls and connect to five different towers. During a conversation, your signal could be switched from one tower to the next; you’ll also be “handed off” to another tower if you travel outside your coverage area while you’re speaking.

Designed for business and not tracking, call detail records provide the kind of information that helps cell companies manage their networks, not track phones.

If I make a cell call from Kenmore Square, in my home town of Boston, you might think that I’m connecting to a cell site a few hundred feet away. But, if I’m standing near Fenway Park during a Red Sox game, with thousands of fans making calls and sending texts, that tower may have reached its capacity. Hypothetically, the system might send me to the next site, which might also be at capacity or down for maintenance, or to the next site, or the next. The switching center may look for all sorts of factors, most of which are proprietary to the company’s software. The only thing that you can say with confidence is that I have connected to a cell site somewhere within a radius of roughly twenty miles.

Aaron Romano, a Connecticut lawyer who says that he has seen many cases involving cell records, has done a series of calculations to show how imprecise these locations can be. If you suppose that a cell tower has picked up a signal from ten miles away, you’re looking at a circle with a radius of ten miles, which has an area of three hundred and fourteen square miles. Cell tower coverage is divided into sectors. Most towers have three directional antennae, each of which covers one third of the circle. Including that factor gives you a sector of 104.67 square miles. “That’s a huge area,” Romano said. “So how can anyone say, with any degree of certainty, that a handset was at the scene of the crime?”

Some technologies can locate you precisely. If you carry an iPhone, you’re also carrying a G.P.S. transmitter, which links to a ground station and then to several satellites, which can find your location to within fifty to a hundred feet. You enable the G.P.S. when you use certain software, such as Google Maps. Similarly, if you make an emergency 911 call, your company will use three towers to triangulate your location; if you’re using a smartphone, it will use G.P.S. to pinpoint where you are.

If you’re the target of an ongoing investigation and law-enforcement agencies want to track you, they can ask a phone company to “ping” your phone in real time. (They also use that technique when trying to find a kidnapping victim.) Those methods are not what’s captured by phone-company cell tower records of the sort that helped put Roberts in prison.

When investigating a crime that occurred in the past, police tend to have two options: seize the G.P.S. chip and download the locations or obtain the cell records. Wednesday’s Supreme Court decision made it mandatory for police to obtain warrants before searching the cell phones of people they arrest. But the case law on getting cell tower information is split. In most jurisdictions, police can obtain your call detail records without a warrant. The disparity in requirements between the two could encourage police to rely increasingly on call detail records, Hanni Fakhoury, a staff attorney for the Electronic Frontier Foundation, said.

Put another way, if I’m making a cell phone call from my couch and someone commits a murder in a bar half a mile away, my cell records may serve as corroborating evidence that I took part in the crime. That might be true if I’d claimed to be in another state at the time, but those records cannot place me next to the body. What they don’t show is the precise location of a cell phone. Yet prosecutors often present those records as if they were DNA.

A few years ago, the F.B.I. established a unit specializing in cell records, called C.A.S.T. (Cellular Analysis and Surveillance Team), with the mission of analyzing cell location evidence. The Bureau declined requests for an interview, but C.A.S.T. agents in recent cases have asserted a different theory of how cell networks operate. Testifying at a trial for murder and robbery in Florida in June, 2013, Special Agent David Magnuson said that the instant a call is received or placed, it’s the phone that decides which tower to go to—not the software that adjusts network load—and that, “ninety-nine per cent of the time, it’s the closest tower.” Although he conceded that cell records can be imprecise, he described them as “like a historical digital fingerprint.” He added that the F.B.I. checks its information by doing periodic “drive tests,” in which it measures radio-frequency information emitted by cell towers to see if the coverage area agrees with its models.

Independent experts I spoke to called this testimony into question—both the accuracy of the estimates and the validity of the drive tests. Conditions are so changeable that, even if a drive test confirms the model on a particular day, it may not on another, and certainly not on a day years in the past. It’s a probabilistic statement, not a scientific one.

In 2012, the U.S. District Court for the Northern District of Illinois ruled that an F.B.I. agent could not testify about the location of a defendant’s cell phone because the analyses did not rise to the level of trusted, replicable science. Other courts have found for the defendant after the defense attorney discredited the prosecution’s expert witness.

Lisa Marie Roberts’s original lawyer wasn’t one of them. There were reasons to suspect her: she had a tumultuous, sometimes violent relationship with the victim, Jerri Williams. Cell records showed that at 10:27 on the morning of the murder, Roberts’s phone connected to a tower within 3.4 miles of Kelley Point Park, where Williams’s body was discovered. Her attorney felt that was enough to convict her.

But she was making that call while driving a red pickup truck more than eight miles away, as confirmed by a witness. The system had simply routed her call through the tower near the park. It also emerged that new DNA evidence placed another suspect, a man, at the crime scene. And another piece of evidence helped: moments earlier, Roberts had received another call that came through a different site. The two towers were 1.3 miles apart. She could not have traveled that distance in the forty seconds between the calls. And so her cell records, in a sense, helped to save her.